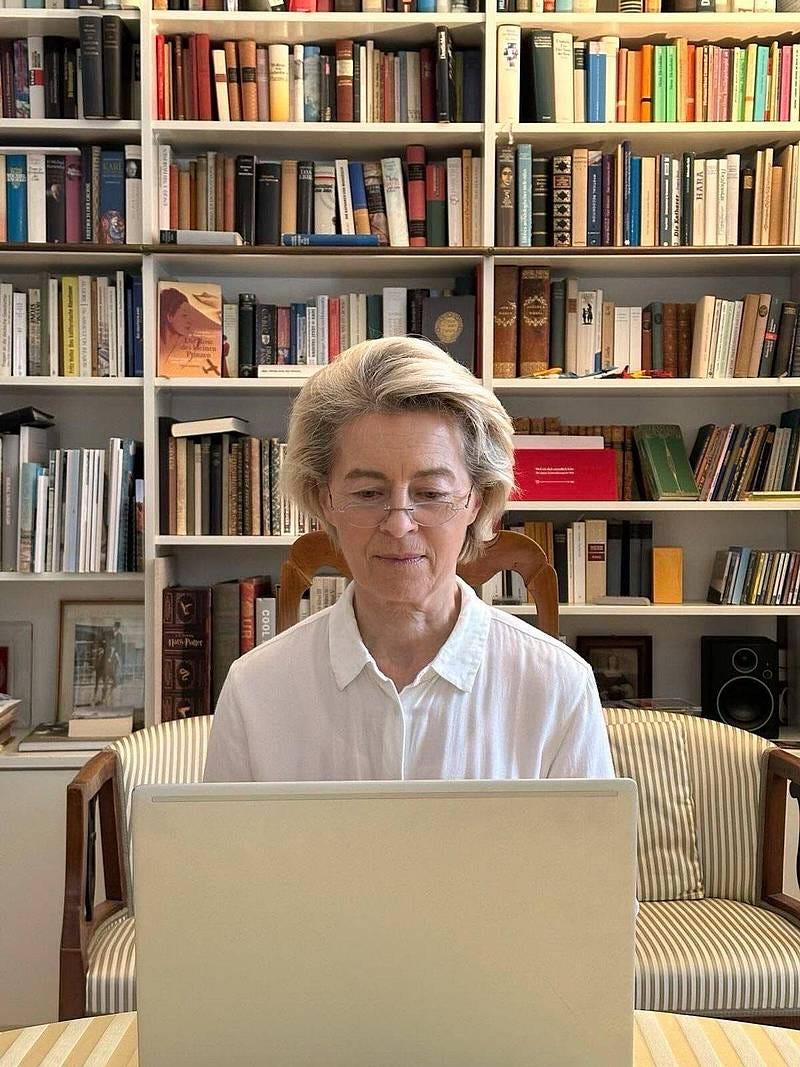

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine may have been the best thing that could’ve happened to Ursula von der Leyen.

Before Russia’s attack, all she had to show for her career was a string of failures as a flailing German politician with no electoral future. Under her leadership as defense minister, the German military was widely criticized for its lack of readiness. She was embroiled in a major scandal over the allocation of multimillion-euro contracts to external consultants. And she faced scrutiny over her doctoral dissertation, with a university commission confirming improper citations. She was cleared of intentional plagiarism but the damage to her reputation was done.

What do you do with someone like that? In German politics, people who are too connected to fire and too unpopular to promote are often shuffled off to Brussels.

There, they can hold a face-saving final post without doing much more damage back home. People like Oettinger, Ramsauer, or Bangemann. All names in the dustbin of history. That’s exactly where von der Leyen was headed — until Russia invaded Ukraine. It was her shot at turning exile into legacy.

Point of No Return

Overnight, she seized control of the European Commission’s identity, transforming it from a rule-keeping bureaucracy into a something resembling a wartime command center with a single mission: total alignment with Kyiv.

Von der Leyen embraced what anthropologist Gregory Bateson called schismogenesis: the process by which groups define themselves through opposition to their enemies. Bateson coined the term while studying tribal rivalries in Papua New Guinea. Communities there locked themselves into endless cycles of one-upmanship, each side exaggerating its identity in reaction to the other. As a result, they’re trapped in a kind of mirror image.

Von der Leyen’s political identity is now fully fused with being anti-Russian. The longer the war drags on, the more determined she becomes. Back in March 2022, she still spoke of “another Russia besides Putin’s tanks,” a Russia that Europe might one day reconcile with. But that kind of language has disappeared. On May 7, 2025 von der Leyen declared: “Russia is a permanent threat for the whole of Europe.”

No more hedging, no diplomatic off-ramp. Russia has become Europe’s forever enemy. And for von der Leyen, there is no turning back.

Betting on a War Dividend

Europe has already paid a steep price. Skyrocketing energy costs from cutting cheap Russian gas have punished consumers and industry alike. Yet instead of seeking a way to manage that fallout, von der Leyen is pushing for more. On Wednesday, the Commission proposed a blanket ban on Russian gas, along with measures to restrict Russian oil and nuclear energy imports into the bloc. Hungary and Slovakia are vocal opponents, with Slovakia’s prime minister warning that the policy amounts to “economic suicide.”

It sounds reckless. But it’s in line with what von der Leyen’s ReArm Europe program requires: a permanent enemy to justify historic spending. The Commission’s €800 billion defense package isn’t just about security. It’s pitched as a rare opportunity to kick-start industrial growth, to unlock what von der Leyen described as “a powerful tailwind for important industries.” All this is about to permanently shift the EU’s balance of power. Let’s unpack what’s at stake.

👀 Reading this from a forwarded email? You can get The Brawl Street Journal straight from the source. It’s free…

Stumbling Auto Giants

ReArm Europe could provide a significant boost for the heart of Europe’s economy: Germany. Its most important industry by far is still the automotive sector, the largest sector in the country by revenue and exports. In 2023, it generated more than €564 billion in sales and directly employed nearly 780,000 people.

Germany’s car industry is in deep trouble. Not just because of energy prices. The real problems go back further: years of complacency, overreliance on Chinese demand, and a late, clumsy pivot to electric vehicles. Rising labor costs and the looming threat of Trump’s tariffs on EU car exports only add to the woes. Volkswagen, for example, is now planning to cut tens of thousands of jobs.

But Germany’s car industry isn’t just about big brands like VW, BMW, or Mercedes. It’s built on thousands of smaller companies in the supply chain.

These aren’t household names, many aren’t publicly traded. But they make the parts, systems, and materials that Germany’s car industry runs on. Highly specialized suppliers with often only a handful of customers that might face no future at all with a shrinking auto industry. For them, ReArm Europe could become a lifeline.

Tanks, Not Cars

Take Schaeffler AG, a supplier of engine components and rolling bearings. It’s seeking partnerships with established defense firms to expand its footprint in the sector. Renk Group AG, known for its transmissions and gear systems, is now the primary supplier of transmissions for Germany’s Leopard 2 battle tank. And Trumpf SE, a leader in automotive photonics, wants to pivot its laser expertise toward high-energy laser system for drone defense.

Of course, even as such firms pivot to tanks, drones, and warships, high energy costs are here to stay. Cutting Europe off from Russian gas for good won’t do much to improve competitiveness. But that’s the great thing about defense. It doesn’t follow the rules of normal consumer markets.

There’s no off-brand Leopard 2. That makes defense an ideal industrial replacement. Price pressure becomes a political question, not an economic one.

These smaller companies aren’t the only ones lining up to benefit, of course. Rheinmetall—which may use a Volkswagen plant to build tanks—, ThyssenKrupp, and Hensoldt are major beneficiaries. And France and Italy have their own defense giants ready to cash in: Thales, Safran, Leonardo.

But there’s a difference. These firms aren’t nearly as deeply woven into their national economies as Germany’s sprawling web of auto suppliers and industrial subcontractors. Germany has far more at stake if this doesn’t work. And obviously, Germany isn’t getting the ReArm lifeline for free. It never works that way in Europe.

The Art of the Brussels Deal

If you look back at the EU’s origins, it was about bargaining from the very start. In the 1950s, France was still a rural economy. Moving millions off the land and into industrial jobs was major effort the Fourth Republic couldn’t manage alone.

The solution? The Common Agricultural Policy. It helped France secure massive transfer payments and internal market taxes from Germany to modernize. In return, Germany got access to French markets to fuel its industrial expansion.

The question now is: What’s the bargain that’s been struck to agree on ReArm Europe? The last few days may offer a clue.

Paris Takes The Lead

Shortly after Merz’s election as chancellor, he and Macron published a joint op-ed announcing that France and Germany would “realign” their energy policies.

For years, pro-nuclear France and anti-nuclear Germany had been at odds over Europe’s energy strategy, clashing in Brussels over investment rules, market design, and what counted as “green.” But now, the message from Paris and Berlin sounds different. Macron declared:

We want an overall vision of the energy markets and investment at the European level in our cross-border networks and infrastructures.

Macron’s optimism points to one thing: France is stepping up to claim energy leadership in Europe. Germany, meanwhile, still wants to shift from natural gas to hydrogen. But until recently, Berlin had blocked any serious role for nuclear-powered hydrogen, insisting on “green hydrogen” made only from wind and solar.

That position has now changed. The German coalition treaty backs hydrogen from “all colors,” a clear signal that nuclear is back in play. And that means France’s nuclear industry just secured a central role in Europe’s energy future.

France could become a major hydrogen supplier to Germany, just as it already is for electricity. By trying to help save Germany’s industrial base, France is cementing its role as Germany’s key energy provider, further boosting its political weight in the EU.

One question remains: whether ReArm Europe will gain traction as planned.

Fear Feeds the Machine

So far, just over half of the EU’s 27 member states have answered the Commission’s call to request more fiscal space to ramp up defense spending. The escape clause allows them to boost military budgets by up to 1.5% of GDP over the next four years without breaching the Maastricht Treaty’s budget rules.

The countries that have signed on so far include Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Slovakia.

No doubt, von der Leyen’s framing of Russia as a permanent threat is designed to pull the rest of the bloc into line. But she can’t force them. The Commission can propose and pressure, but in the end, national governments still control the purse strings.

Europe is placing a massive strategic bet: that it can survive without cheap Russian energy by transforming itself into a war economy. Whether that’s a sustainable strategy or just a self licking ice cream cone Keynes would call growth depends on whether you count success in GDP points alone.

The likely outcome is deeper deindustrialization and a political backlash that could wipe already weak leaders like Merz off the map entirely.

Nevertheless, von der Leyen likely carved her name in history as the first to push for a truly post-Maastricht industrial policy. The price? Turning the EU from a peace project into a machine that needs enemies to survive. Bateson knew you can’t win a cycle of schismogenesis by engaging within its rules. You can only step out of it. Von der Leyen isn’t even trying.

Send this to the last person who said the EU’s economic madness has no method!

📨 People in boardrooms, energy desks, and hedge funds keep forwarding this. Stop getting it late — subscribe now!

Already subscribed? Thanks for helping make BSJ quietly viral.

Time for some chemistry lesson, maybe stuff for another post: it’s corrosive and leaks very easily. How is hydrogen used. How is it transported? As a gas ? Liquified at extremely high pressure and/or low temperature? Ad a compound it would typically require Carbon, which would make it natural gas…

Macron betting on hydrogen to make France an energy superpower? That’s an idea so staggeringly stupid that he probably jumped on it and grabbed it with both arms before some other EU politician could beat him to it.