🇬🇱 Greenland's Strategic Triangulation

Why 1 Billion Tons of Minerals Could Be Greenland’s Ticket to Independence

Pituffik in Greenland is the northernmost U.S. military base. Due to its unique location at the “Top of the World”, the base plays a critical role in missile warning, missile defense, and space surveillance missions.

Today, about 200 active-duty U.S. Air Force and Space Force personnel are stationed there—down from 10,000 troops deployed during the Cold War. For perspective, Greenland’s entire population currently stands at just 57,000.

The U.S. presence in Greenland dates back to a 1951 agreement between the U.S. and Denmark, which granted the U.S. the right to build military bases and move forces freely across the island. This arrangement was born out of an earlier, more audacious proposal: In 1946, President Truman offered $100 million in gold, along with rights to a patch of Alaskan oil, to purchase Greenland outright.

Unlike Trump’s infamous bid to buy the island, Truman’s proposal was conducted under Cold War secrecy. There was no public spectacle—and no official rejection.

Given that the U.S. has enjoyed virtually unrestricted military access to Greenland for decades, Trump’s renewed interest in acquiring the island likely had little to do with defense strategy.

Instead, Greenland’s true value lies beneath its icy surface.

Greenland’s Underground Riches ⛏️

A 2023 survey showed that 25 of 34 minerals deemed “critical raw materials” by the European Commission were found in Greenland. They include rare earth elements, graphite, platinum group metals, and niobium.

When it comes to critical minerals, China doesn’t just dominate the market—it owns it. They produce approximately 98% of the world’s gallium, 82% of natural graphite, and 60% of processed rare earth elements. This overwhelming reliance on Chinese exports poses a significant risk of geopolitical extortion for both the U.S. and the European Union.

In a bid to reduce dependence on China, the EU took its first step toward tapping Greenland’s resource potential by signing a Memorandum of Understanding in November 2023 for a strategic minerals partnership with Greenland:

The high resource potential for CRM [critical raw minerals] and other Raw Materials in Greenland combined with EU's demand for minerals and expertise in prospecting, exploration, extraction, processing and refining, makes a solid base for the Partnership and supports the development of Greenland's mineral resource sector as a future supplier of CRM and other Raw Materials to the EU.

A Memorandum of Understanding doesn’t create any rights and obligations, but the EU’s desire to get a piece of the cake is clear.

Against this backdrop, it’s clear why Denmark has no intention of selling Greenland—to the U.S. or anyone else.

Denmark has controlled the island for centuries, first as a colony and now as a semi-sovereign territory within the Danish realm. However, in 2009, Greenland was granted broad self-governing autonomy, including the right to declare independence through a referendum.

The independence movement remains strong, fueled by growing resentment toward Denmark. In 2022, revelations surfaced that Danish doctors had forcing birth control on teenage girls in Greenland during the 1960s and 1970s. To this day, Greenlanders report facing racial discrimination from Danes.

The renewed interest in Greenland places its people in an unexpected position of power. As Bloomberg describes it:

Its new position gives it the ability to play the US and Denmark off of each other – a dynamic that might ultimately see it come out on top.

But there’s one more player in this game, beyond the U.S. and the EU.

The West is Late to The Party ⌛️

China has been trying to gain a foothold in Greenland long before Trump first floated the idea to buy the island in 2019.

Here’s a partial timeline of China’s efforts to expand its influence in Greenland.

2012 | China’s Minister of Land and Resources visits Greenland

2014 | First Memorandum of Understanding between Greenland Minerals and Energy (GME) and China Non-Ferrous Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering and Construction Co. (NFC)

2015 | Minister Qujaukitsog talks about airport, port, hydroelectric and mining infrastructure development with Sinohydro, China State Construction Engineering, China Harbour Engineering

2016 | Danish government stops Hong Kong-based General Nice from taking over the abandoned naval base Gronnedal

2017 | Prime minister visits China

2018 | China Communications Construction Company bids to build airports in Greenland, prompting Danish government to finance half of the airports

In July 2021, Denmark adopted two laws aimed at preventing foreign investments and economic agreements—mainly Russian and Chinese—that could pose a threat to national security. Denmark pressured Greenland to adopt similar laws, but Greenland resisted.

In fact, Greenland might try to play all the interested parties against each other to secure the best possible deal for itself.

Geopolitical Jiu-jitsu You Wouldn’t Expect From a Small Island 🥋

An ongoing legal dispute highlights how Greenland is carefully balancing its relationships, ensuring it neither angers the West nor alienates China. Let’s take a closer look.

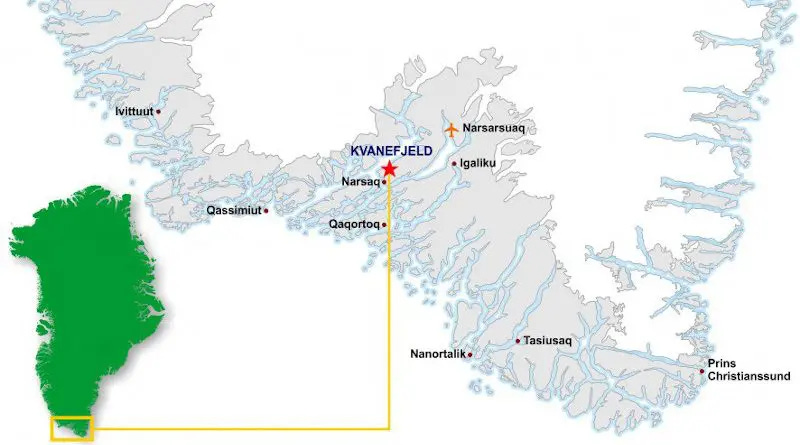

Kuannersuit (Danish: Kvanefjeld) is home to a vast ore body of rare earth elements, with estimated 108 million tonnes of ore reserves and over 1 billion tonnes of mineral resources. This deposit is believed to be larger than the European Union’s largest known rare earth deposit in Sweden.

It was in Kuannersuit that Greenland Minerals (GM), a wholly owned subsidiary of the Australian mining company Energy Transition Minerals (ETM), began operations under an exploration license in 2007. The company’s goal was to assess the presence of rare earth elements in the Kuannersuit area and evaluate the feasibility of mining operations.

As uranium and rare earth metals coexist within the same mineral deposits in Kuannersuit, extracting rare earth elements inevitably involves the simultaneous mining of radioactive materials.

That’s why the project’s fate shifted with Greenland’s national election on April 6, 2021.

The left-wing environmentalist party Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) won by a landslide. Muté B. Egede, a vocal critic of the Kvanefjeld project, became the new Prime Minister. Shortly after the election, the Greenlandic Parliament passed the “Uranium Act,” which bans the prospecting, exploration, and exploitation of uranium.

The day after the election, GM’ shares fell by 44%.

In response, GM initiated arbitration proceedings against the Governments of Greenland and Denmark in 2022. The arbitration focuses on the right to mine, with GM claiming that the Act deprives the company of its entitlement to an exploitation license.

GM is seeking either confirmation of its right or $11.5 billion in compensation—a sum nearly four times Greenland’s annual GDP.

Despite 2.5 years of arbitration, no significant progress has been made. The Governments have only filed a defense on jurisdiction, without making any substantive comments on the core issues.

But this case gets even spicier.

The Art of the Deal ♠️

About 10% of GM is owned by Chinese rare earth giant Shenghe Resources, which is partly state-owned. In other words, moving forward with this project would effectively give China control over one of the world’s largest rare earth and uranium mines.

The government opposed Kuannersuit not due to Chinese influence, but out of concern that radioactive waste from uranium extraction could jeopardize the local population’s access to essential resources, such as clean water.

However, GM had been through and passed an environmental inquiry. The obvious way to fight the project would’ve been to challenge the relevant permits—not to enact a retroactive law that exposes Greenland to massive damages claim.

Creating a dubious law and leaving it in limbo seems more like a tactic to avoid solidifying irreversible facts.

Right now, Greenland is almost certainly looking to drag out the arbitration proceedings to buy time. Time to see if it can strike the best deal with the U.S., the EU, or China.

Remember, Greenland hasn’t implemented a law to prevent investments from China. It could easily do so, just as it passed the Uranium Act. But a savvy dealmaker keeps all options open—without alienating any one party.

And Greenland will need a good deal to achieve independence anytime soon.

Greenland is financially dependent on Denmark, which provides $500 million annually in subsidies. Exploiting its underground riches is one of the few ways to replace these funds.

This will require all the help Greenland can get. Due to its remoteness, harsh climate, and lack of infrastructure, only substantial investments can bring these rare earths to market. Greenland also has only a limited workforce and a virtually non-existent mining industry, making it reliant on foreign labor.

Developing this industry is crucial to Greenland’s path toward becoming a fully autonomous nation-state.

But it’s far from certain whether it will choose the U.S., the EU, or China as its partner.

Good write up