💥Let's "Activate" a Non-Existent Market

Where will the €3 billion flooding into "renewable fuels of non-biological origin" end up?

There’s a lot of money to be made with renewable fuels in the next few years. But not just any renewable fuels: Renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs).

If you’ve never heard of RFNBOs, you’re not alone. RFNBOs are hardly known because no one’s producing them in any meaningful quantity.

The reason this industry is virtually non-existent is simple: there’s neither sufficient supply nor demand. But when the market doesn’t produce the results EU economic policymakers envision, they call it a “market failure.” And under EU economic law, a “market failure” justifies throwing billions of euros at the problem.

It’s the same with RFNBOs. To kickstart production, Germany and the Netherlands have launched a €3 billion scheme to support RFNBO production worldwide—a plan recently approved by the European Commission.

With so much government money about to flood the market, plenty of players will be eager for a slice of the pie. Let’s dive into the details.

What Are RFNBOs Exactly? 🔥

RFNBOs are liquid fuels—such as ammonia, methanol or e-fuels—produced from renewable hydrogen. They’re primarily intended for transport sectors that can’t be electrified, like maritime shipping and aviation, but could also, in theory, be used for road transport.

Hydrogen forms the foundation of all RFNBOs. When combined with other molecules (like CO, CO₂, or N₂), it creates more complex chemical products, such as ammonia, methanol, or e-fuels. However, not just any hydrogen will do. By definition, RFNBOs require the “green” stuff.

This Hydrogen Must Have the Right Color ♻️

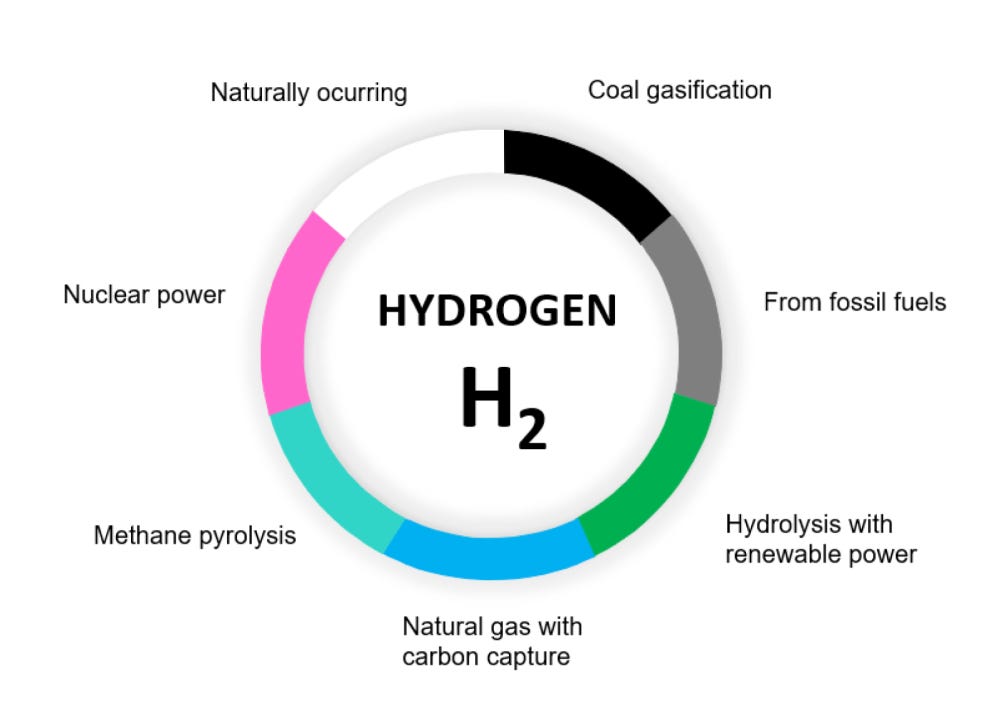

Hydrogen can be produced in several ways—using natural gas, coal, nuclear power, and more. These methods are color-coded: blue, black, pink, and so on.

But the key word in RFNBOs is “renewable,” which means only “green” hydrogen fits the bill. Green hydrogen is produced through electrolysis, a process that uses electricity from renewable energy sources to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

While Germany and the Netherlands boast a combined wind power capacity of roughly 81 GW and solar capacity of about 105 GW, it’s neither economically nor technically feasible to rely solely on this power for green hydrogen production. That’s why the €3 billion scheme includes plans to build at least 1.875 GW of electrolysis capacity worldwide.

Is 1.875 GW a lot of capacity?

The world’s largest green hydrogen project in Ordos, China, has a capacity of 390 MW. This European scheme aims for a production capacity nearly 5X larger.

So yes, 1.875 GW is a lot of generation capacity.

And it will require even more wind and solar capacity to make it work. Because green hydrogen projects generally require about 2 MW of renewable energy for every 1 MW of electrolyser capacity.

The combined wind and solar capacity of Germany and the Netherlands would need to be 20X higher to support the electrolysis capacity they aim at.

So how do you kickstart a practically non-existent RFNBO sector? With a lot of cash, of course.

Which begs the question:

Who Will Pocket These €3 Billion?🤑

All that money will be awarded through a double auction system:

RFNBOs producers and buyers will each name a price. Producers offering to sell RFNBOs at the lowest price and buyers willing to pay the highest price will be awarded contracts under the scheme.

The €3 billion will fill the funding gap between the two prices.

And filling this gap will definitely be necessary. Because RFNBOs like green ammonia are very expensive:

Ammonia made from natural gas (represented by the violet bars in the chart below) can be as cheap as $410 per metric ton (mt), while ammonia made from green hydrogen is as expensive as $1,053/mt. (The turquoise bars in the chart below shows the cost of blue ammonia, produced using sequestered CO₂.)

In case you’re wondering why we’re comparing ammonia prices instead of hydrogen prices, it’s because a global (green) hydrogen infrastructure doesn’t exist. The market is highly fragmented, making price comparisons meaningless. Buyers can’t simply switch to cheaper hydrogen—there’s no practical way to transport it.

Currently, there are only about 5,000 km of hydrogen pipelines worldwide. To put that into perspective: The combined length of the world’s oil and gas pipelines is more than 1.18 million km (730,000 miles)—enough to circle the Earth 30 times.

Transporting hydrogen with ships or trucks is both complex and costly, which is why it’s rarely done. For storage, hydrogen has to be compressed to around 350 to 700 times atmospheric pressure as a gas, or cryogenically cooled to -253°C as a liquid.

Ammonia, by contrast, is denser and easier to handle. It only requires compression to 10 times atmospheric pressure or chilling to -33°C. Plus, ammonia has been a key feedstock for mineral fertilizers for over a century, meaning international shipping routes and a well-established infrastructure for its transport are already in place.

That’s why long-distance transportation of hydrogen is only feasible via the ammonia detour. However, converting hydrogen into ammonia and then ammonia back into hydrogen is very energy-intensive. This round-trip results in a total energy loss of 40-50%, which partly explains the unfavorable economics of RFNBOs.

But hey, it’s just a “market failure”! Let’s throw enough money at this problem and it’ll disappear.

Just kidding. It won’t.

But that doesn’t mean bureaucrats won’t spend €3 billion in a cage fight with physics…

They call it “market activation”

Germany launched a pilot scheme similar to this in 2021, with a budget of €900 million.

The first €300 million part of the pilot tender, which began in 2022, has recently concluded. Under this scheme Germany will buy at least 259,000 mt of green ammonia between 2027 and 2033 from UAE-based fertilizer maker Fertiglobe (FERTIGLB.AD).

Here’s how the whole operation is set up:

Fertiglobe’s supply of renewable hydrogen will come from Egypt Green Hydrogen, a consortium between Fertiglobe, Scatec ASA, Orascom Construction, the Sovereign Fund of Egypt, and the Egyptian Electricity Transmission Company. The project is in the Suez Canal Economic Zone.

The electricity used in the production process will be generated in a newbuild onshore wind park of 203 MW located in Ras Ghareb close to the Red Sea and a newbuild solar PV plant of 70 MW in Africa’s largest solar complex located in Benban in the south of Egypt.

The renewable ammonia will be transported to storage tanks at Ein El Sukhna Port via an existing seven km pipeline. The seaborne delivery to Europe will be overseen by Fertiglobe International Trading, a wholly owned subsidiary of Fertiglobe PLC. The renewable ammonia will be delivered to the Port of Rotterdam.

It’s still unknown who the electrolyser supplier will be.

Of course, all the companies and banks involved in the project tirelessly invoked the mantra of a “sustainable future” at the close of the project. We can expect a lot more press releases like this in the future.

The ammonia under this scheme will cost €1,000/mt ($1,042/mt) for delivery to Northwest Europe. Again, ammonia made from natural gas is less than half as expensive (€392/mt or $410/mt).

This price difference will create another problem…

Scammers Are Getting Ready to Roll 🦹♂️

There’s a huge incentive for fraudsters to mislabel non-green ammonia as the real green deal and sell it for a hefty premium.

Biofuels policies in both the EU and the US have already opened the floodgates to billion-dollar fraud schemes. There’s no reason to assume it won’t be the same with RFNBOs.

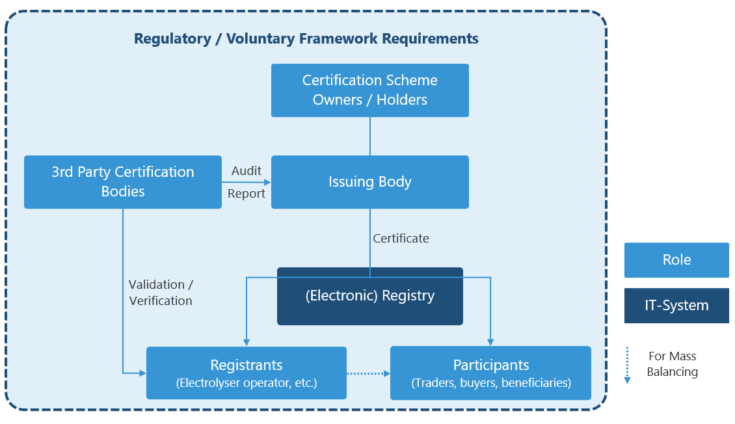

To address this issue, the EU wants to establish an auditing and certification system under the latest Renewable Energy Directive (RED III). I won’t bore you with the details on how such a system could be set up. But if you happen to work in this industry, it’s time to start marketing your services to potential clients.

There is a clear business opportunity for auditing firms, especially as EU regulations tighten. Firms that can address gaps in expertise, technology, and regional coverage have significant potential to carve out a niche in this growing market.

Of course, this isn’t the only business opportunity that comes out of all this.

What’s in it for Lawyers and Investors?

Opportunities for Lawyers ⚖️

The demand for legal counsel during and ahead of the auction process is likely going to be massive.

Interest in Germany’s 2022 pilot auction—where Fertiglobe was the winning bidder—was already significant. Lot 1 had a €300 million volume (the remaining €600 million are up for grabs later) but attracted over 1,000 interested parties from 65 countries across five continents. Twenty-two companies submitted non-binding bids, five entered negotiations, and one emerged as the winner.

This new scheme involves ten times more funding.

Lawyers in that sector should focus their marketing efforts on reaching companies that might consider bidding.

The scheme aims to build at least 1.875 GW of electrolysis capacity, open to projects with a minimum of 5 MW of electrolyser capacity. In theory, that could be as many as 375 different projects.

There will be substantial business opportunities in this sector, ranging from joint venture negotiations to compliance and regulatory issues, both within the EU and in non-EU countries where the ammonia will be made.

Opportunities for Investors 🏦

Investors should monitor sectors with increased demand opportunities in the relevant regions. Wind and solar installations in these areas will need to be built, electrolyser capacity will need to grow, and infrastructure for processing and shipping ammonia, methane, and e-fuels must be developed or expanded.

Nothing’s Stopping This Money Train

There are plenty of reasons to be skeptical about this entire effort. In fact, the European Court of Auditors has said the EU's green hydrogen goals are not realistic.

But that doesn’t change the fact that the willingness to spend €3 billion is very real. Germany will contribute €2.7 billion to the scheme, while the Netherlands will contribute €300 million.

It’s unlikely that a CDU-led government after the February snap elections in Germany will pull the plug. Conservatives seem just as excited about green hydrogen as Green party members are.