Sanctions Come Home

How the EU is exposing itself to escalating damage.

On December 15, the European Union added an unusual name to its sanctions list: Jacques Baud. He is a retired Swiss army colonel, a former member of Swiss strategic intelligence, and served as a policy chief for United Nations peace operations. Baud has written and spoken extensively about the war in Ukraine, often challenging official narratives.

Being placed on the EU sanctions list amounts to a form of civil death within the European legal space. Member states are required to prevent the sanctioned person’s entry into, or transit through, their territories. All funds and economic resources held or controlled by the person must be frozen. No funds or economic resources may be made available to them, directly or indirectly.

With Baud living in Brussels, the implications are particularly punitive. Buying groceries or paying rent quickly becomes impossible.

The decision was not imposed following a court proceeding or a decision by an independent judge. It was administered directly by the Council. Baud could, in theory, attempt to challenge the designation in court. But doing so with frozen assets renders this right largely symbolic.

Normally, sanctions are directed at those responsible for serious breaches of international law which the sanctioning authority seeks to end. In this case, that would be Russia’s waging of war against Ukraine. How does Jacques Baud contribute to Russia’s behavior? According to the Council Decision:

Jacques Baud […] acts as a mouthpiece for pro-Russian propaganda and makes conspiracy theories, for example accusing Ukraine of orchestrating its own invasion in order to join NATO. Therefore, Jacques Baud is responsible for, implementing or supporting actions or policies attributable to the Government of the Russian Federation which undermine or threaten stability or security in a third country (Ukraine) by engaging in the use of information manipulation and interference.

Interestingly, the same claim Baud is accused of making was voiced in 2019 by Oleksiy Arestovych, then an adviser to the President of Ukraine:

Of course a large scale war with Russia and joining NATO as result of defeat of Russia. The coolest thing.

It is easy to argue that banning speech that simply echoes statements by former Ukrainian government insiders will have no deterrent effect on Russia’s conduct whatsoever. But the sanctions’ implied objective appears closer to Mao’s dictum: punish one, educate a hundred.

The problem here goes well beyond freedom of expression. Limiting discussion does not only harm the individual subjected to the restriction. It is a special case of institutional rot: an indication that the system is beginning to suppress inconvenient information rather than process it.

The EU’s habit of self-defeating decisions is nothing new. What is new is that the system is now increasingly insulating itself from any error-correcting feedback mechanism. A Council decision taken just days before Baud’s sanctioning, this time concerning frozen Russian assets, reveals the same pattern at a larger scale. The development is on track to dismantle the foundations of the continent’s prosperity from within. Let’s head to Brussels to see how.

On December 12, the EU agreed to indefinitely freeze Russian central bank assets held in Europe. EU ambassadors invoked an emergency clause—one that does not require unanimity among member states—allowing the assets to remain frozen for as long as an “immediate threat to the economic interests of the Union” is deemed to persist. Until now, EU member states had been required to vote unanimously every six months to renew the freeze.

The move is a legal workaround designed to erase the risk that Hungary or Slovakia might at some point refuse to roll over the measures, potentially forcing the EU to return the assets to Russia. In effect, the decision has been locked in, and along with it, the possibility of renewed debate over whether the legal conditions for maintaining the freeze continue to be met.

This measure was only a precursor to the EU’s decision, taken Thursday night, to lend €90 billion to Ukraine. With Belgium’s prime minister, Bart De Wever, opposing the outright seizure of Russian assets held at Euroclear in Brussels, the EU opted for a solution that is only marginally less problematic: issuing debt on capital markets, secured against untapped spending capacity in the bloc’s shared budget, to fund Ukraine for the next two years.

While the worst possible outcome—outright seizure—has been averted, Russia’s sovereign assets nonetheless remain frozen indefinitely. According to European Council president António Costa, Ukraine would only have to repay the loan after Russia has paid reparations. Under this arrangement, Russian assets would remain immobilized and could ultimately be used to repay the loan should Moscow refuse to pay.

Whether this wobbly legal contraption will survive any contact with arbitration reality is highly doubtful. Yet given the EU’s efforts to keep inconvenient opinions out of its decision-making process, it is almost certain that from here on current leaders will only double down on this path, regardless of how self-defeating that posture ultimately proves to be. Any moral satisfaction the indefinite asset freeze may generate is outweighed by its predictable fallout.

The glib argument in favor of using Russian assets—one even some serious professionals make—goes roughly as follows: Russia broke the law first, so why should we care about the law now? However, adherence to law is not ultimately about benefiting others. It is about benefiting yourself. By voluntarily restricting your own future options, you signal that you will not change the rules mid-game when circumstances shift. This is what makes you a reliable partner others want to do business with. Once corrupted, restoring that signal can take decades.

As argued on these pages before, the consequences are higher public financing costs and lower foreign direct investment. But the erosion can easily be read as spreading through the system. Baud’s case and the asset-freeze charade are merely two symptoms that outside actors can interpret as endemic. Actors who discover that rules can be suspended when they become inconvenient in one area will rationally assume they can be suspended elsewhere as well.

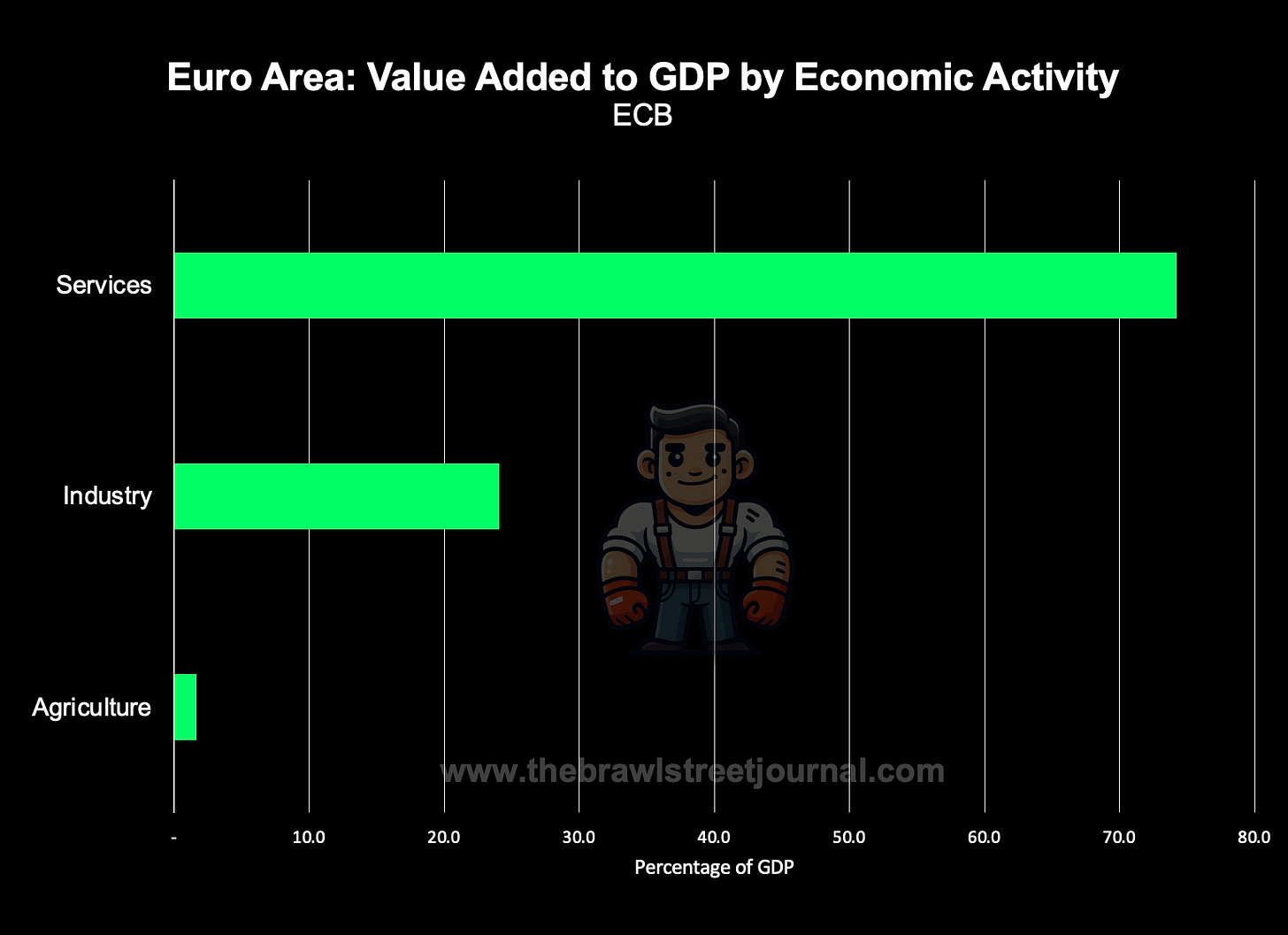

Europe’s prosperity is unusually dependent on activities that require legal predictability: services, financial intermediation, custody, insurance, arbitration, and cross-border contracting. The service industry is one of the EU’s most important productive sectors. In 2024, it exported €1.57 trillion worth of services to non-EU countries.

Russia’s economy, on the other hand, is not. A big chunk of Russian income is generated through physical exports—above all energy—where revenues depend on delivery rather than trust in foreign legal systems, and where exposure to punitive measures has already been internalized. In other words, similar actions do not impose similar costs. A system that lives off services and credibility is structurally more vulnerable to legal erosion than one that lives off commodities.

And then there is the risk that your example becomes precedent. Whatever rule you relax for yourself, others will reuse against you, just with different values and narratives. As Robert Volterra, one of the world’s leading public international lawyers, puts it:

What happens if a great power rejects the EU’s environmental policy, declares it contrary to international law, and then begins seizing the sovereign assets of EU member states?

Unsurprisingly, Russia has announced retaliatory measures ahead of the EU’s loan plan agreed on Thursday. The Kremlin has already seized or frozen the assets of at least 32 Western companies in response to earlier disputes, causing losses of at least $57 billion, according to the Kyiv School of Economics Institute. These moves may be only the opening salvo in a broader play—one that other actors could find it convenient to align with if doing so advances their interests.

For all the talk of a “rules-based order” that EU elites have invoked in recent months, they display strikingly little awareness of how quickly they are running it into the ground. Undermining internal error correction by sanctioning voices who might tell them so only invites external error correction—in the form of economic selection pressure.

Sharing this article keeps inconvenient feedback in circulation!

📨 People in boardrooms, energy desks, and hedge funds keep forwarding this. Stop getting it late — subscribe now!

Already subscribed? Thanks for helping make BSJ quietly viral.

“A system that lives off services and credibility is structurally more vulnerable to legal erosion than one that lives off commodities.” - never thought about it this way, but makes so much sense

The elimination of the “rules based order” to save the “rules based order” feels an awful lot like the “our democracy” movement.