Crossing the Black Line

Germany shows the first cracks in the renewables consensus

Expanding coal use is not a position normally voiced by mainstream politicians in Europe. Yet that is what Michael Kretschmer, minister president of the German state of Saxony, called for in a recent interview.

The timing explains the shift. Germany’s gas storage has fallen to a historic seasonal low of 25%, and without mild weather, gas rationing becomes a realistic risk. Kretschmer’s proposal is striking because Germany’s conservatives spent the last fifteen years advancing an energy policy practically indistinguishable from the Greens—a trajectory sealed by Angela Merkel’s post-Fukushima decision to phase out nuclear power. Had those plants remained online, coal would not even be part of today’s debate.

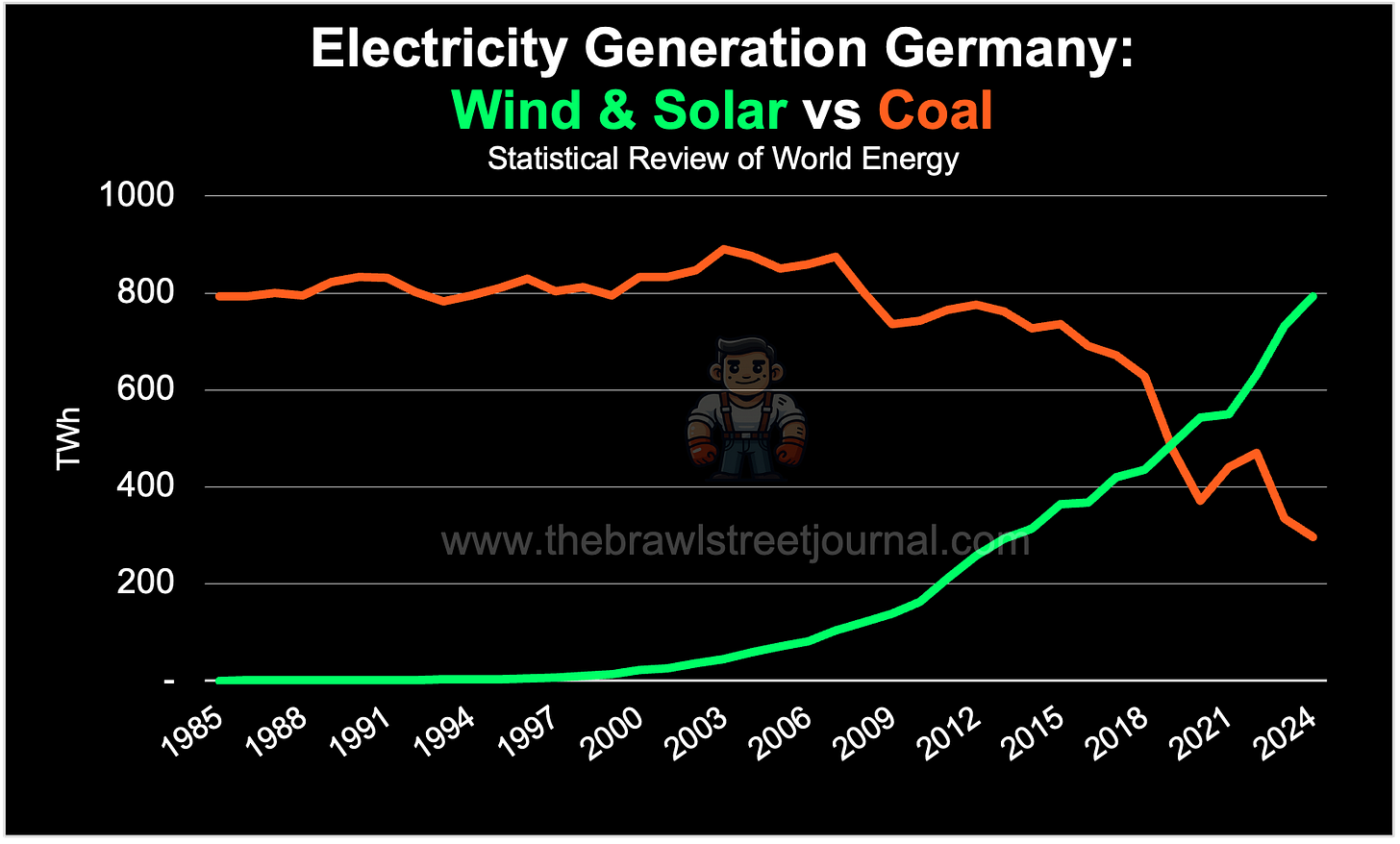

But this is where Germany finds itself today. And viewed in isolation, the idea of burning more coal does not sound irrational. The country’s contribution to global CO₂ emissions is barely a rounding error, and its ratio of wind and solar to coal would remain favorable even if coal use increased.

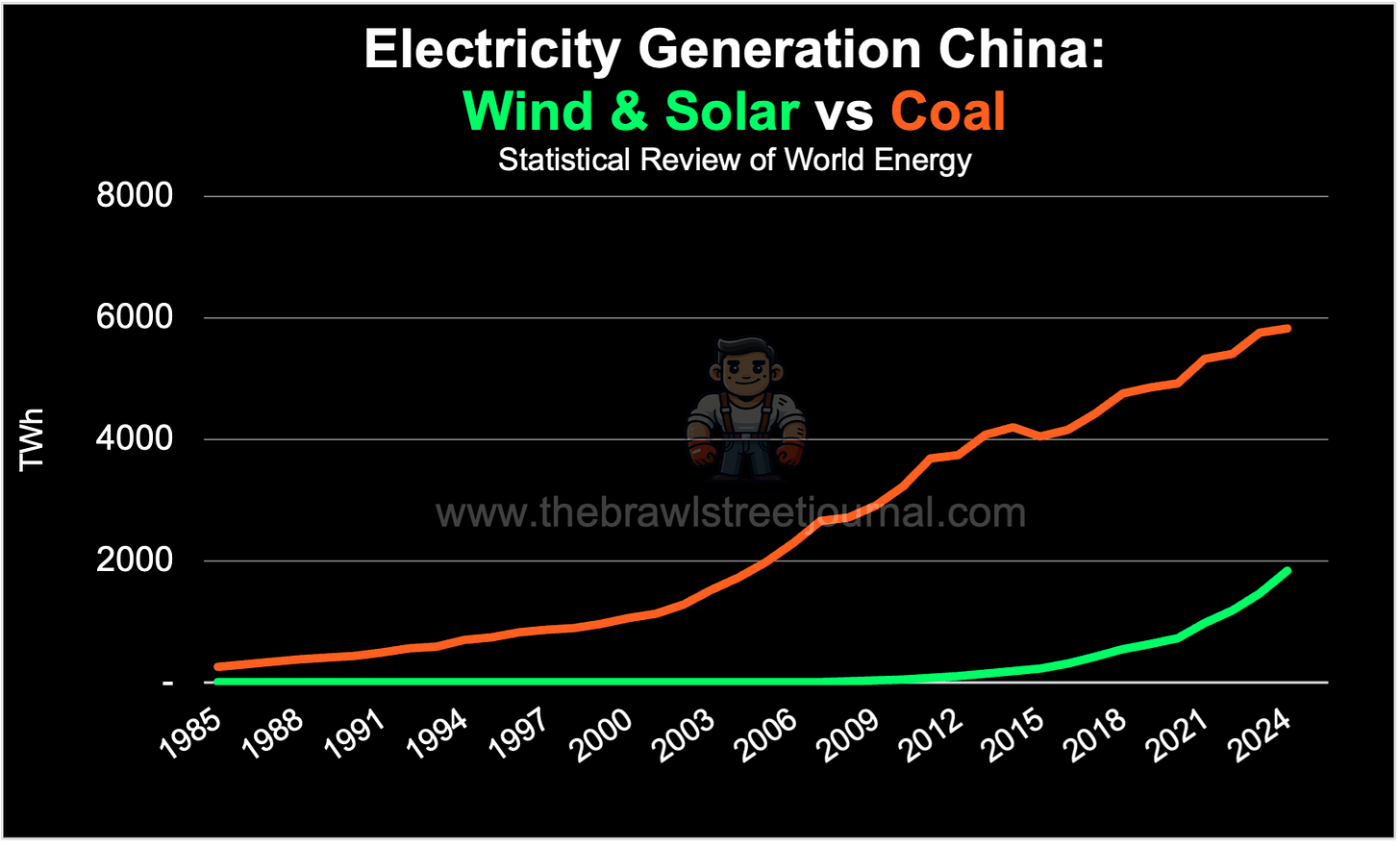

Especially when compared with China, the world’s largest coal consumer.

Kretschmer’s suggestion should be palatable to carbon counters. He pointed to the argument that LNG can be just as climate-damaging as coal. One widely cited study claims that U.S. LNG’s greenhouse-gas footprint is 33% higher than coal’s. The reason lies in methane leakage during extraction, processing, pipeline transport, and especially liquefaction and shipping. Methane is commonly claimed to have more than 80 times the warming impact of CO₂ over a 20-year time horizon. Taken at face value, this would appear to give coal the perfect cover.

From a “strategic autonomy” point of view, coal could, in theory, reduce Germany’s dependence on LNG to a meaningful extent. By my math, using data from the Statistical Review of World Energy, replacing gas-fired generation with coal could cut Germany’s gas demand by roughly 15–20% of annual consumption.

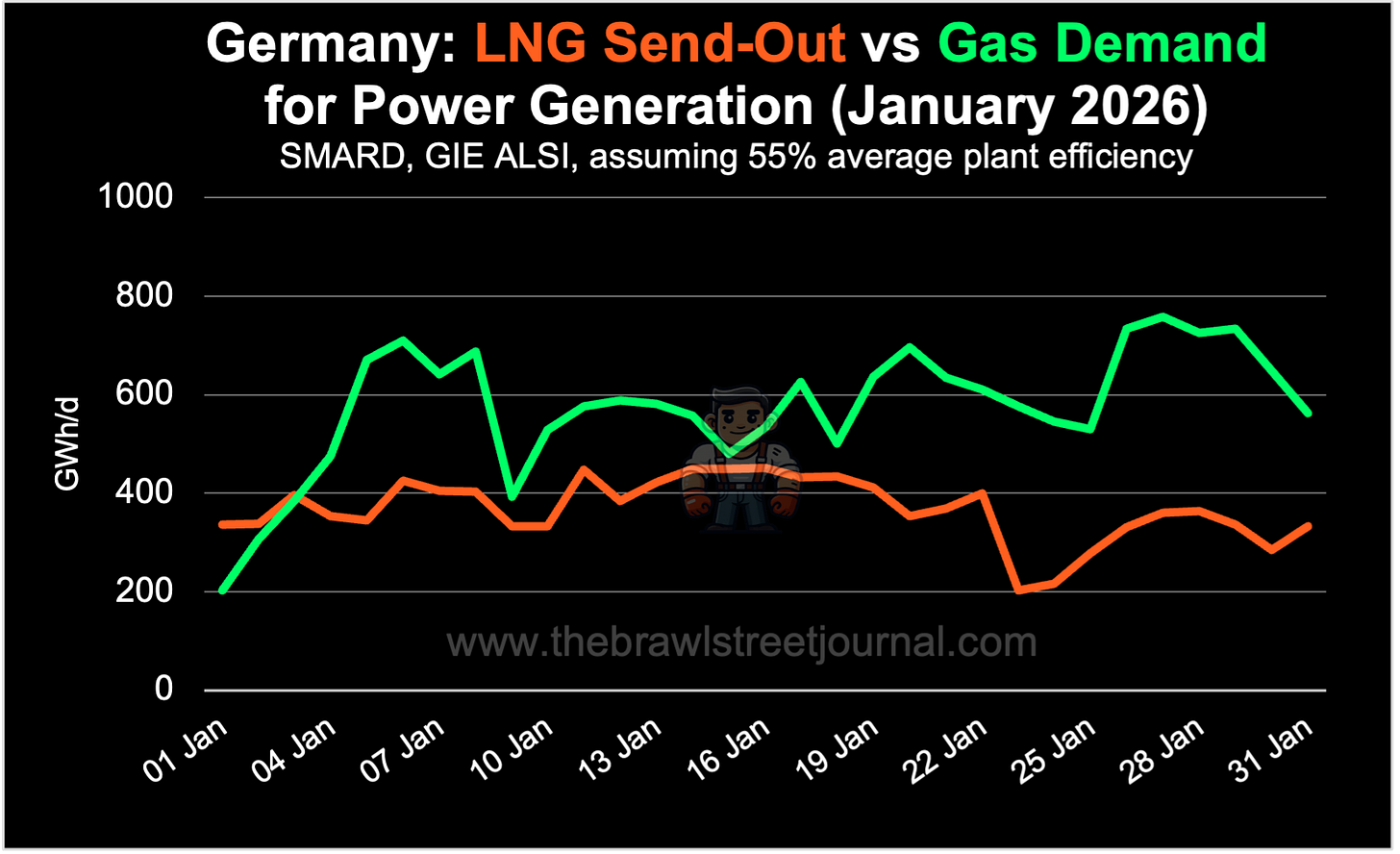

Germany’s position as an energy vassal to whichever gas supplier appears the least problematic villain at the moment—Chancellor Merz recently travelled to Qatar in search of higher volumes—becomes most visible in winter. In January, LNG send-out into Germany’s gas grid was energy-equivalent to roughly 64% of the gas input required for power generation. Even if all LNG volumes had been directed to the power sector, they would not have been sufficient to cover total gas demand for electricity production.

On the tightest day of the month, LNG send-out covered only 35% of the gas needed for power generation. Let’s examine whether domestic coal could be a way out of this energy trap.

On paper, the potential for coal in Europe is enormous. According to the Statistical Review of World Energy, the EU held 78.6 billion tonnes of proved coal reserves as of 2020, the majority of them in Germany and Poland. With current EU coal consumption at 306 million tonnes per year, that stock would be sufficient to supply the bloc for more than 250 years.

But not all coal is equal. It comes in two distinct forms: lignite and hard coal. Around 200 million tonnes of lignite are burned in Europe per year, compared with just over 100 million tonnes of hard coal.

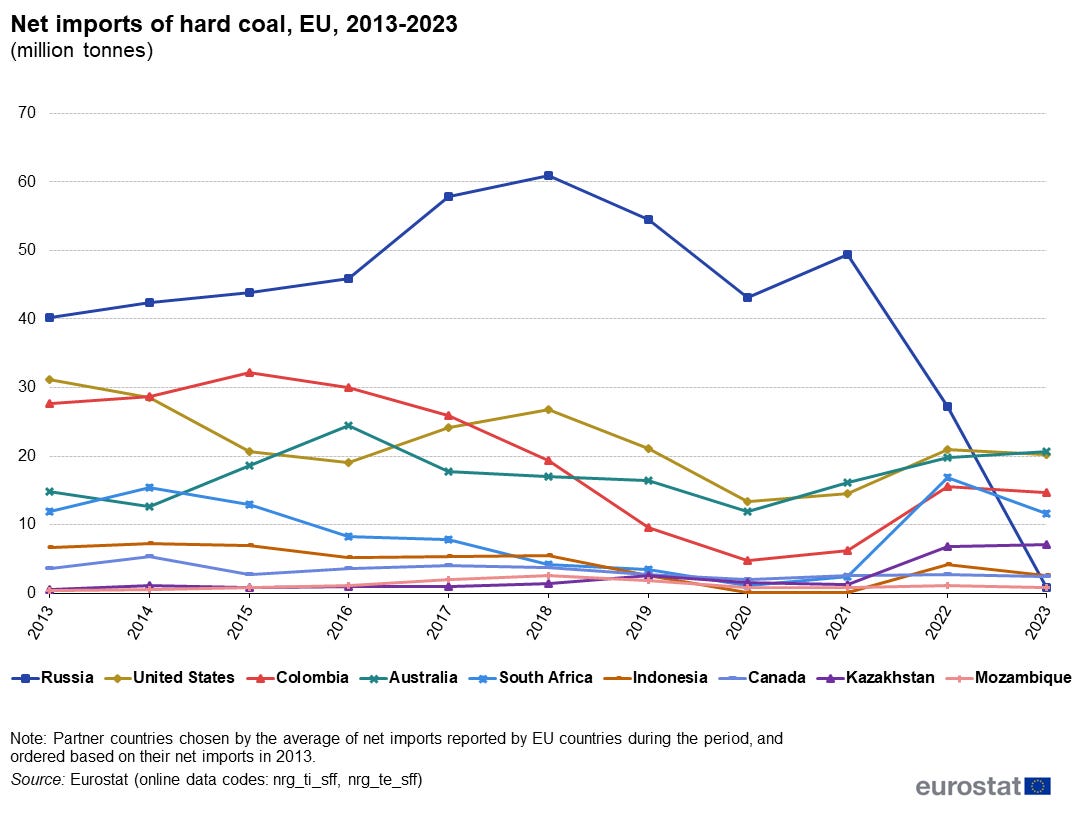

Due to its low energy density and high moisture content, long-distance shipping of lignite is uneconomical. Hard coal, in contrast, is internationally traded. More than 60% of the hard coal consumed in Europe is imported—until the Ukraine war predominantly from Russia, and also from the United States, Colombia, or Australia.

Lignite is typically burned at power plants located near the mines—so-called “mine-mouth” operations. Because lignite accounts for the majority of Europe’s proven coal reserves, it is mostly this type of coal that offers anything close to real energy autonomy.

An obvious problem persists: coal is polluting and lignite even more so than hard coal. Lignite emits higher levels of CO₂, dust, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides. While filters and scrubbers can significantly reduce the latter pollutants, trace elements like mercury persist.

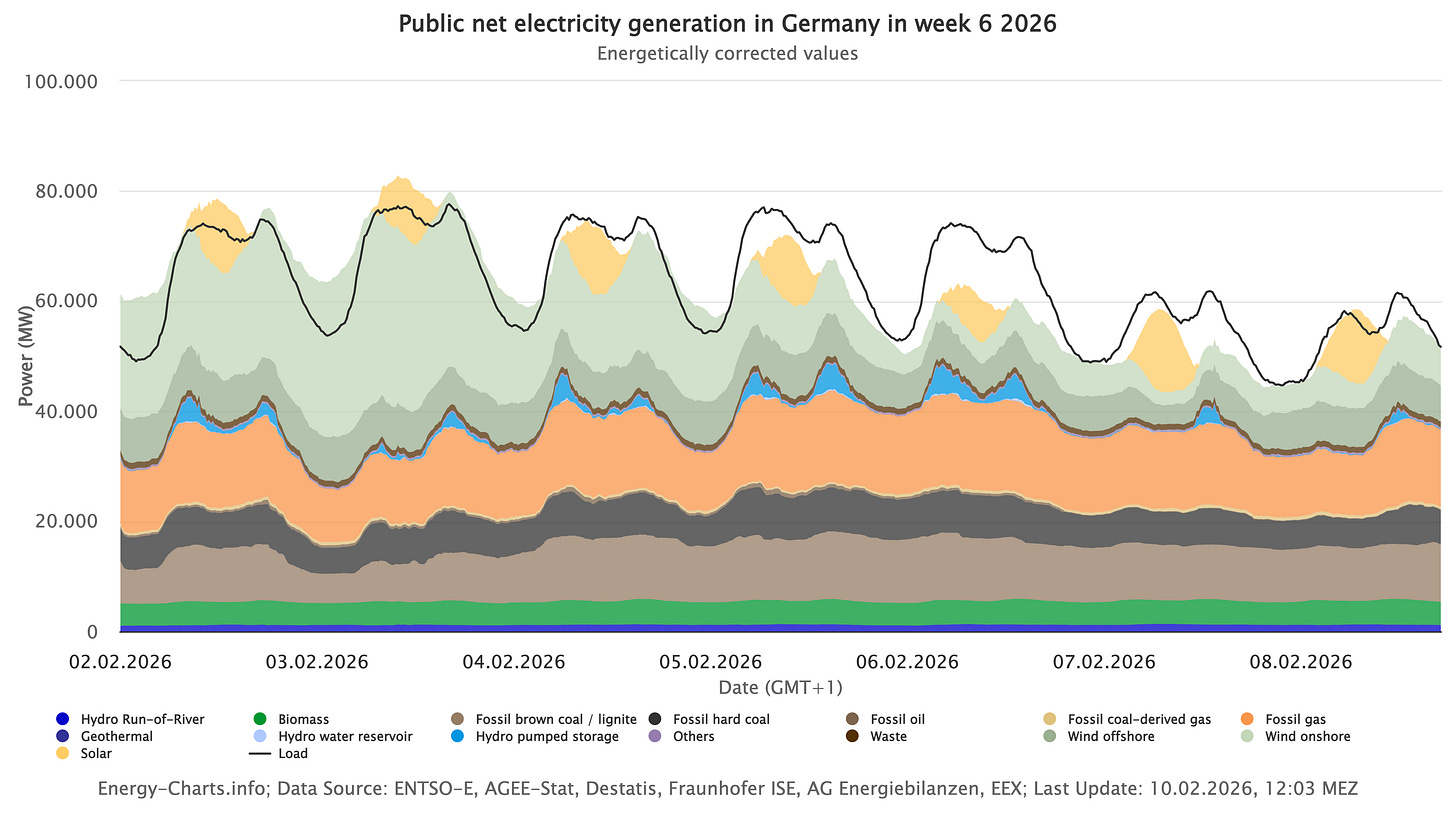

Technological advances may further limit the local environmental harm of burning coal, but overcoming those obstacles is beside the point. The way coal fits into a grid increasingly shaped by renewables makes it an inefficient solution regardless. Both coal and gas need to follow the actual load patterns that wind and solar are incapable of matching. Coal, however, can do so only to a limited degree, as weather-driven generation causes large swings in output.

The reason is response time. Coal plants must be heated carefully to avoid thermal stress: a cold unit may need six to ten hours or more to synchronize to the grid, and even a warm plant typically requires several hours to reach full load. Once running, modern coal units can adjust output by roughly 2–5% of rated capacity per minute at best. Gas turbines, by contrast, can ramp tens of megawatts per minute, with smaller units responding almost instantaneously.

There is a second constraint: minimum load. Coal plants often cannot reduce output below roughly 25–40% of rated capacity without risking flame instability. Gas turbines can shut down entirely or operate at much lower minimum loads, allowing far finer control.

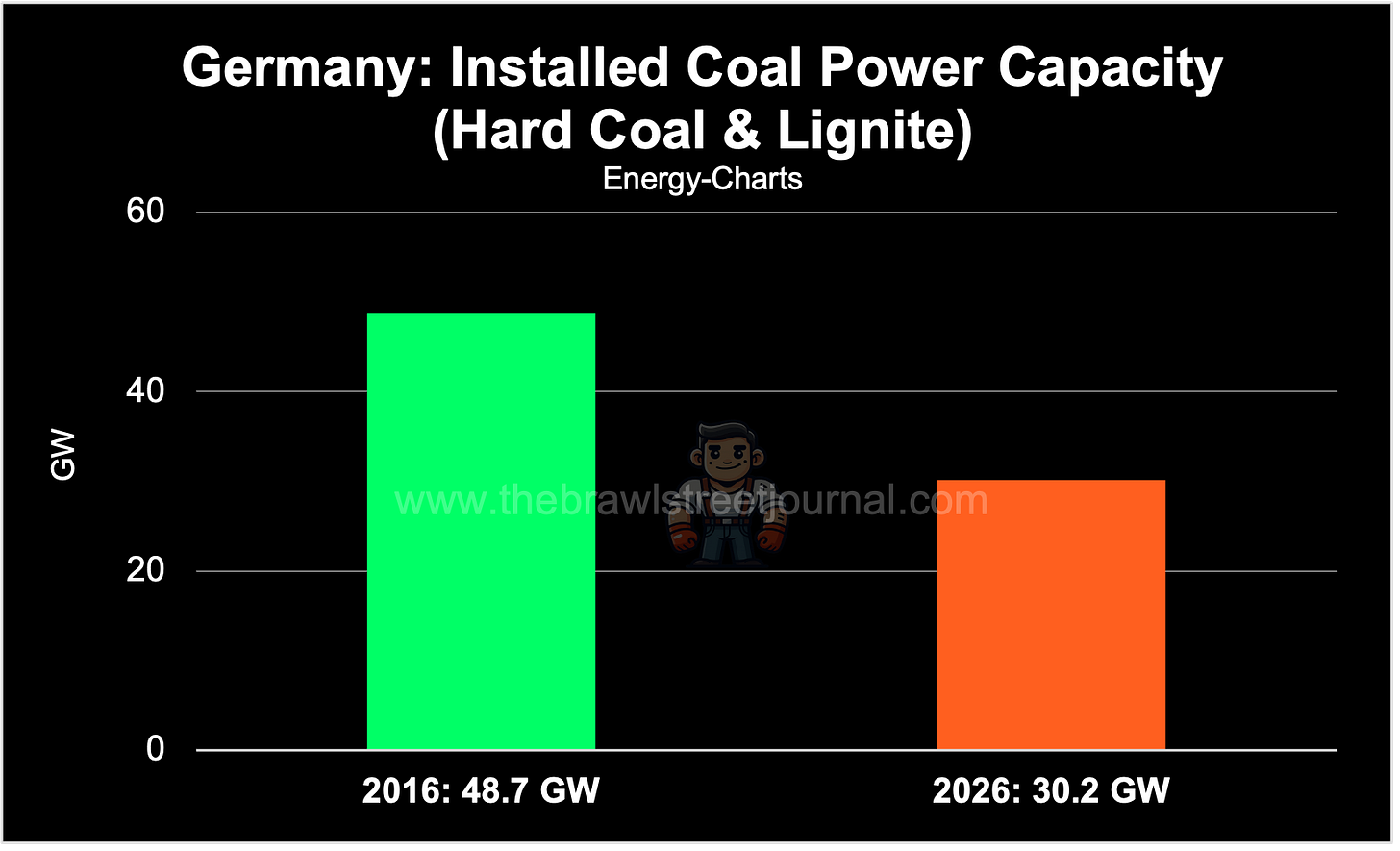

Coal plants, designed for steady output, are pushed into stop-start operation, long idle periods, and low capacity factors. With CO₂ pricing added to the mix, it has become increasingly difficult to run them profitably, and closures have accelerated over the past decade: lignite capacity fell from 21 GW in 2016 to roughly 15 GW today, while hard coal declined from 27 GW to a similar level.

Yet separating market forces from political design is difficult, since the legally mandated coal phaseout through 2038 has paid operators billions to close plants that might otherwise have continued operating.

This has produced a peculiar outcome. Billions were paid to close plants that might have kept running while other plants are now paid simply to remain available, waiting to stabilize the grid when needed. Retiring thermal capacity with one hand and subsidizing idle thermal capacity with the other is the inevitable result of forcing dispatchable power to follow the residual load left behind by intermittent generation. The subsidy treadmill, sold for a quarter century as “transition support,” now defines the system.

The straightforward solution, from a strategic-autonomy perspective, would be to eliminate intermittent generation capacity. Baseload plants could operate in a capital-efficient manner, rather than costing taxpayers billions as a form of weather insurance. Yet the legal principle of protection of legitimate expectations renders that option largely unworkable. Wind and solar installations get a guaranteed feed-in tariff for the duration of 20 years.

Even if new addition of capacity were stopped today, the grid would still have to accommodate this nuisance generation. In the end, gas dependency at the margin isn’t going away, even if coal usage would be increased by getting rid of carbon pricing as suggested by Kretschmer.

However, a first sign of recalibration emerged this week: a draft from the office of Economics Minister Katherina Reiche could significantly slow the addition of new renewable capacity. The proposal would grant distribution network operators the authority to designate so-called “capacity-limited grid areas.” These designations could remain in place for up to ten years.

The trigger would be grid congestion: if curtailment exceeded 3% in the previous year, operators would be permitted to impose the limitation. In these “capacity-limited” areas, not only would redispatch compensation be eliminated, but the right to grid connection would also be suspended.

Unsurprisingly, the green-tech industry has already gone up in arms against the proposal, an understandable reaction, given that its business model depends largely on continued capacity additions, regardless of system-level effects. The center-left coalition partner SPD is hardly enthusiastic either.

Yet a proposal like this, coming from a government that until now never seriously questioned the “energy transition” narrative, marks a remarkable shift from previous thinking shaped by the assumption that simply adding more wind and solar would resolve the system’s constraints.

It will undoubtedly take a long time before these admissions have tangible consequences. But alongside Kretschmer’s proposal to return to coal, this month may come to mark the moment when the mainstream consensus around the renewable model began to give way in Europe’s largest economy. Physics dictates that this fracture was never a question of if, only when.

Share this with anyone who thinks Europe’s energy debate has no exit ramp!

BSJ continues on X between newsletters — charts, fragments, and early ideas. Following me there is the easiest way to help BSJ grow and reach the right people:

See you there!

YES, it was only a matter of time. Green policy is just grand, until things don't work and go cold, and energy prices increase like mad. Even some politicians start to understand then.

Great article.

And a hopeful sign that reality-based economic policy might make a comeback in Germany.