Gas Without Slack

Why Trump is positioned to dictate terms on Greenland

Europe’s position in the fight over Greenland is almost as baffling as President Trump’s. Mining rare earths and mineral deposits there may never be economically viable, and Europe’s security interest in controlling the island is already covered by NATO, an alliance the EU insists on clinging to even as Washington is busy unravelling it.

The opposition to Trump’s equally perplexing insistence that he must own Greenland therefore seems driven less by strategic substance than by the fact that his bluntness leaves EU leaders no choice but to save face by pushing back. Yet the more Europe pushes back, the more obvious it becomes how ineffective its tools for opposing Trump really are.

While NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte appeared to defuse tensions with a nebulous draft framework agreed with Trump, the fact remains that, just a day earlier, Trump had insisted he wanted “right, title and ownership” of Greenland. And although he later walked back his threat to impose 10% tariffs on six EU countries, plus Norway and the UK, his mercurial style leaves little doubt those threats could quickly return if negotiations drift off script.

In response, Brussels has indicated its willingness to reach for its so-called “trade bazooka,” officially the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI). It includes customs duties as well as restrictions on imports and exports, services and investment, intellectual property, and financial services.

But the bazooka fires at glacial speed. Its activation can take up to a year, spanning investigations, negotiations, consultations, and a vote. U.S. Treasury Secretary Bessent dismissed the threat with a quip about “the dreaded European working group.”

Another problem is that Trump targeted only six EU member states. Yet deploying the ACI requires a qualified majority: at least 15 member states representing 65% of the EU’s population. Given how easily the measure could backfire—and how certain the second-order effects within Europe would be—many states have every incentive to block its activation. Some would even benefit from the tariffs at the expense of the targeted countries. Under these conditions, the ACI is a threat that looks like a bluff, and everyone can see the cards on the table.

Europe appears to have one hope: the Supreme Court. Whether the U.S. president has the authority to deploy tariffs this way is currently the subject of a pending case. Yet even if the Court were to strip Trump of his tariff weapon, it is far from clear that this would be Europe’s salvation.

Trump has another instrument that is perfectly timed for maximum pain at this moment: LNG. The United States supplies almost 60% of the bloc’s LNG. Europe is still in the winter months, and a sudden supply shock would be harrowing. The gas system is already running tight, with minimal redundancy and multiple single points of failure that give Trump escalation dominance. Time to take a closer look at Europe’s current gas situation.

With its high dependence on imported natural gas, the EU is energy-subordinate. According to the Statistical Review of World Energy and Eurostat, the bloc consumed 323 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2024, of which 273 bcm were imported. To protect against supply shocks and price spikes, member states rely on underground gas storage. But storage levels are currently low.

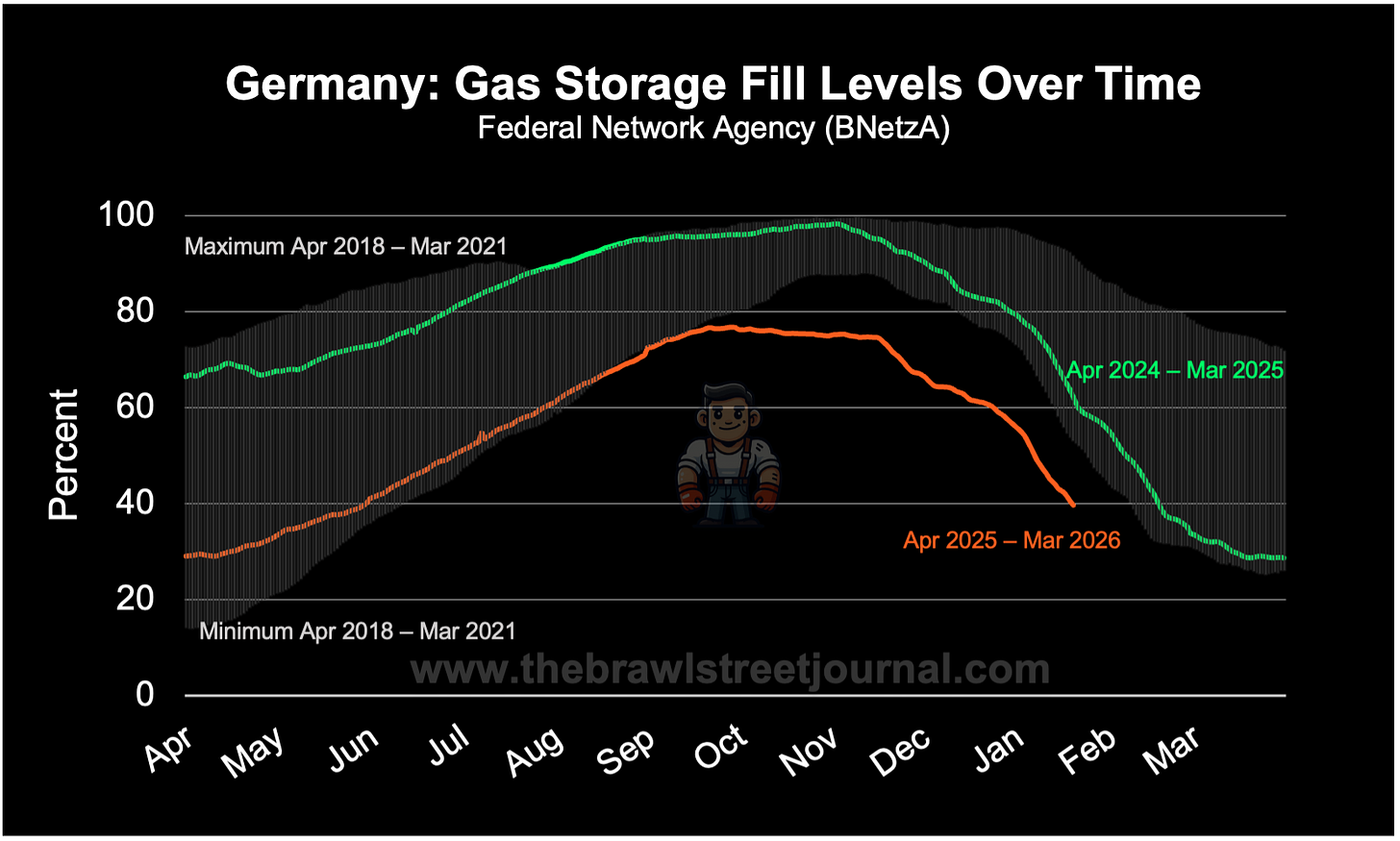

Germany is in the most dramatic position. As of January 23, its gas storage stood just below 40%, well below the seasonal average. The situation is similar across the bloc: EU-wide storage stands below 47%. Europe entered the winter with low levels because gas storage is designed closer to an arbitrage model than to a strategic reserve.

Gas is injected in the summer and sold in the winter, and the system depends on the summer–winter spread being wide enough to justify tying up capital for months. Last year, that spread collapsed, so little gas went into storage. Winter security in Europe is a commodity trade and sometimes the trade doesn’t pay.

How quickly storage depletes is directly correlated with temperature, so the speed of depletion now depends on the weather in the coming weeks. According to the latest modelling published this week by INES—the association of German gas storage operators—average to warm temperatures would lead to moderate to significant withdrawals, with the statutory minimum storage level of 30% still being met.

In an extremely cold winter such as the reference year 2010, however, storage would be fully depleted by mid-February 2026 at current consumption levels. In that scenario, demand could no longer be fully covered.

As a result, consumption would need to be reduced. Germany developed the “Gas Emergency Plan” for such cases, which allows the government to declare an “emergency stage.” This stage allows for the restriction of gas usage by “non-protected customers,” primarily industrial customers. The economic consequences are significant. Natural gas is used as a feedstock in a wide range of industries, for example as a basis for producing chemicals such as paints, coatings, and adhesives, or for the manufacture of fertilizers.

The Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) would issue orders on a case-by-case basis depending on the specific circumstances (storage levels, weather conditions, achieved savings, required lead time for shutdowns, etc.). Rationing can also be structured according to the system relevance of individual sectors. In short, the emergency plan cuts industrial production to protect households, leaving companies such as Bayer and BASF facing a rough start to the year.

The chances of any of this happening are significantly above zero, since polar vortex dynamics are currently forecast to bring unusually cold conditions to northeastern and central Europe through early February.

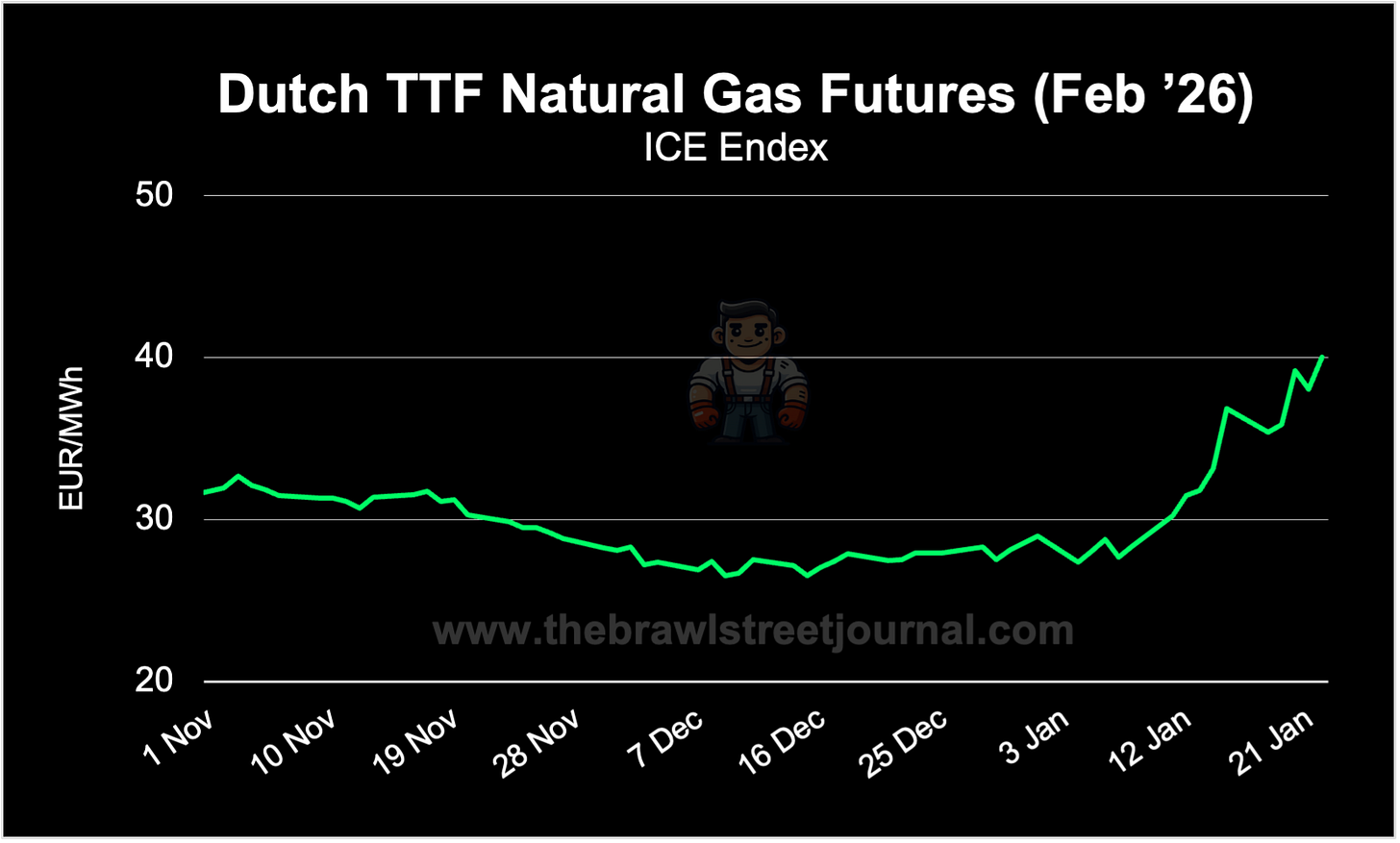

The dependency on American LNG in such a scenario is obvious. But even in mild weather the system has very little slack. INES modelling assumes that LNG keeps flowing. If the United States halted exports, storage would be drawn down quickly even without a deep winter. It may have been more than just the weather that drove Dutch TTF—the benchmark used to value Europe’s marginal LNG cargoes—higher as U.S.–EU tensions over Greenland flared.

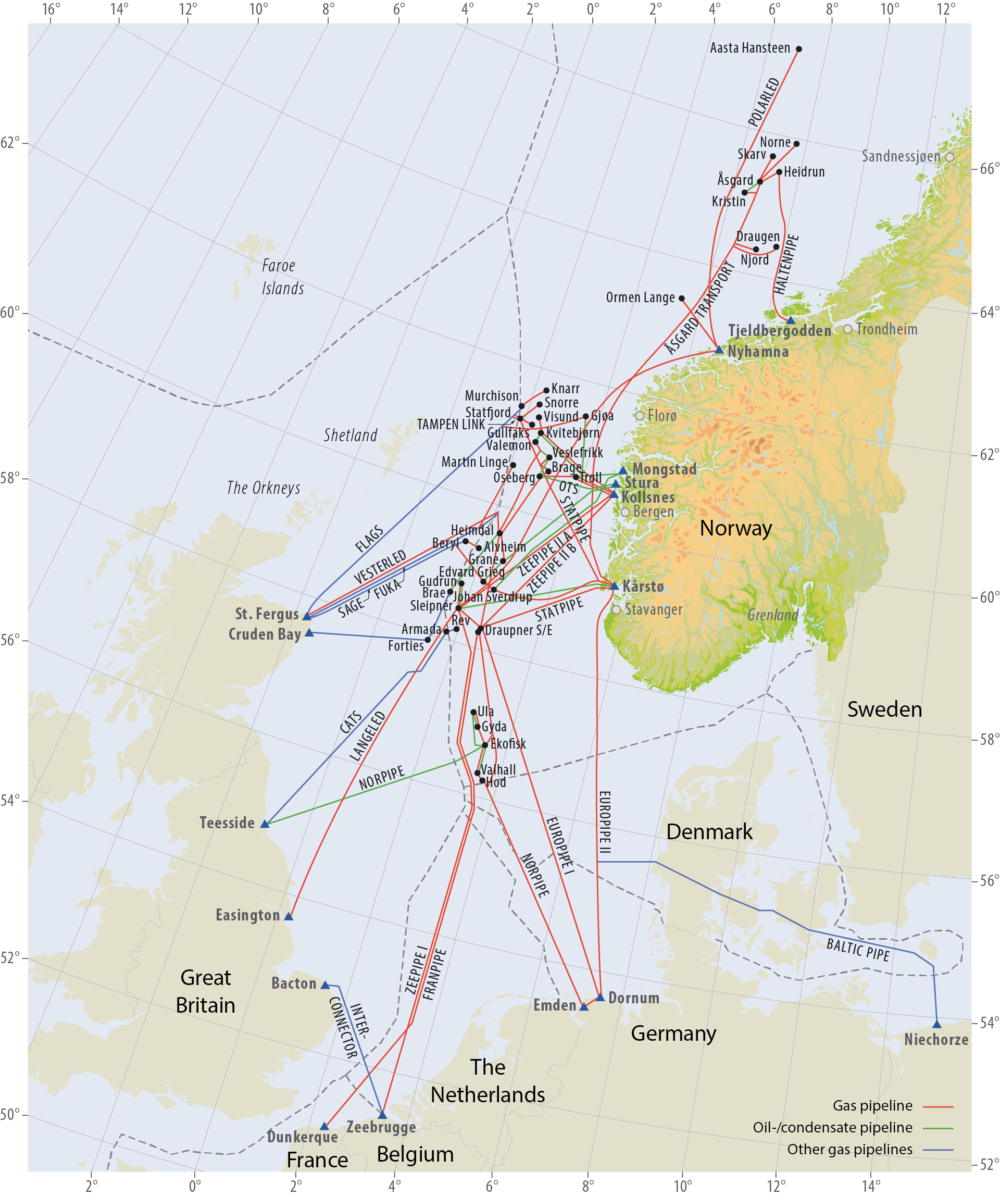

While additional LNG from suppliers such as Qatar could, in theory, offset part of a U.S. shortfall, replacing a supplier that accounts for roughly 60% of Europe’s LNG during a cold winter would be extraordinarily difficult. The other major pillar of the EU’s gas supply is Norwegian pipeline gas. That system, however, is already running at full capacity.

Norway supplies the EU and the UK through seven pipelines with a combined export capacity of almost 367 million cubic meters (mcm) per day. In winter, Norway’s export system typically runs in the range of 335–355 mcm/d, occasionally peaking near 360 mcm/d—close to full utilization—leaving virtually no surge capacity.

Norway’s export infrastructure is also highly centralized. A handful of onshore processing hubs—Kollsnes, Kårstø, and Nyhamna—handle the bulk of gas before export. Kollsnes alone processes roughly 40% of Norway’s gas exports. An outage at that facility would instantly remove nearly half of Norwegian supply, a shortfall no other route could fully backfill.

Recent years have seen multiple incidents—including the Nyhamna shutdown in June 2023 and a compressor failure at the Troll field in May 2025—that temporarily curtailed Norwegian deliveries and triggered price spikes on the Dutch TTF gas market. In a system running without slack, such disruptions will be felt immediately.

The Trump administration must be well aware that Europe has no redundancy and that a single failure could trigger a serious supply crisis. That makes this a uniquely opportune moment to apply pressure over Greenland. The lever exists, and it does not even need to be pulled to be effective. The threat alone may suffice.

Domestically, pulling it could in fact prove attractive. This week, Henry Hub—the U.S. benchmark for natural gas—almost doubled as a cold wave gripped large parts of the United States. As Doomberg noted, curbing LNG exports to suppress domestic prices would not be an irrational move for a president heading into an election cycle.

Meanwhile, Europe’s decision to ban Russian energy imports entirely from 2027 onward has short-sightedly stripped it of optionality. Technically, Russian gas flows could be ramped up. One Nord Stream pipeline survived, Yamal remains intact, and TurkStream continues to deliver gas to Turkey and onward to countries such as Hungary, Serbia, and Bulgaria via its Balkan extensions.

But backtracking from the narrative that it is a moral imperative to stop buying Russian energy—and that this would somehow cripple Russia’s economy—has become politically impossible. Doing so would shred the political identities almost all EU leaders have constructed for themselves in recent years. Once again, European elites have painted themselves into a corner. This time, it leaves them with little room to refuse whatever Trump demands—over Greenland or anything else—in the weeks ahead.

Share this with anyone who thinks TACO applies here!

📨 People in boardrooms, energy desks, and hedge funds keep forwarding this. Stop getting it late — subscribe now!

Already subscribed? Thanks for helping make BSJ quietly viral.

All this, and you didnt even mention the CSDDD, which has ruled Qatar out of sending gas because the EU is so committed to net zero. It seems that at the current pace, they will, indeed, achieve net zero as the entire continent and its inhabitants cease to exist given the lack of available energy.

good luck to you there

The lesson is energy abundance and diversity. The US has it. Europe lacks it and is cutting the few remaining options it has.

To an extent, this is an age old problem for Europe. Pre-Ukraine conflict, Russia exerted a similar leverage by limiting gas flows of gas through pipelines traversing certain countries.

The UK for a while was insulated from this. Large gas fields and onshore coal fields created a sort of moat, even as gas cannibalised the coal fields through price competition (aided by external coal imports). Now with short gas supplies and open gas/electricity interconnectors, the UK is fundamentally linked to the EU energy insecurity problem. The current Government’s doubling down on North Sea ban just makes the problem worse in the long term.

It’s time to promote the UKs energy industries to invest to get us back to energy abundance. If that means limiting some of the interconnector flows, just as the US can limit LNG flows, then that’s what it takes. Energy Abundance is Energy Security.