The current Israel-Iran war has the potential to put Europe in the hurt locker. Regardless of whether Trump chooses to strike, the conflict is likely to drag on for weeks or even months. The economic pressure point in this conflict is the Strait of Hormuz. If the fighting spills over into this vital artery, it could tear open a lot of problems Europe has tried to patch over in recent times.

Some argue that closing the strait would be suicidal for Iran, since its own allies would suffer most from any disruption. Others claim this whole scenario is moot because the Iranian regime is as good as gone. But you don’t need a formal blockade from Khamenei or anyone else for things to unravel. The real issue is perceived risk and insurance.

Panic Premium

Since Israel’s strike last week, the cost to charter large carriers through the Strait of Hormuz has more than doubled. Not because of an actual blockade but because of fear. A pure risk premium.

Hapag-Lloyd, the German shipping giant, calls the threat level at the Strait “significant” and admitted things could shift “in a very short” time. “War quotes” are now valid for just 48 hours, giving insurers room to hike rates in real time.

In the chaos of war, it takes just one move by a state or non-state actor—a rogue missile or a false flag—to make the Strait uninsurable. Lloyd’s syndicates are already reviewing coverage, some are considering pulling out entirely. Without insurance, tankers won’t sail. The odds of a full shutdown may be moderate, but the fallout for Europe’s energy landscape could be massive. Let’s explore what’s at stake.

👀 Reading this from a forwarded email? Subscribe to The Brawl Street Journal to get it straight from the source…

No Detour

Roughly 25% of the world’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) flows through the Strait of Hormuz, most of it from Qatar, one of the world’s largest LNG exporter. For LNG, there is no alternative route once Hormuz is impassable.

Even though Europe doesn’t rely heavily on Qatari LNG in volume terms, having provided 13% of the EU’s imports in Q4 2024, any supply shock would impact Europe well beyond these shipments. Because if Qatari cargoes can’t reach Asia, Asian buyers will go hunting elsewhere. As a result, competition between Asia and Europe for alternative LNG will intensify.

The effects of a supply disruption won’t be linear: a 25% shortage doesn’t mean a 25% price increase. When supply is tight and demand is inelastic prices can easily spike. That’s what happened in 2022. The Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF)—a virtual trading point for natural gas, serving as the primary benchmark for European gas prices—peaked well above €300/MWh to lure cargoes away from Asia. For reference: right now, the TTF is at €41/MWh.

Granted, the effect was particularly pronounced in 2022: Europe lost 45% of its gas supply coming from Russia almost overnight. But the mechanics today are the same and they could unfold fast. Because right now, Europe must fill its natural gas storage.

Winter is Coming

Europe has to hit a 90% gas storage target before winter. Gas isn’t just for winter heat, it’s also the backup when wind and solar fail to deliver during a Dunkelflaute, a period with little sun or wind.

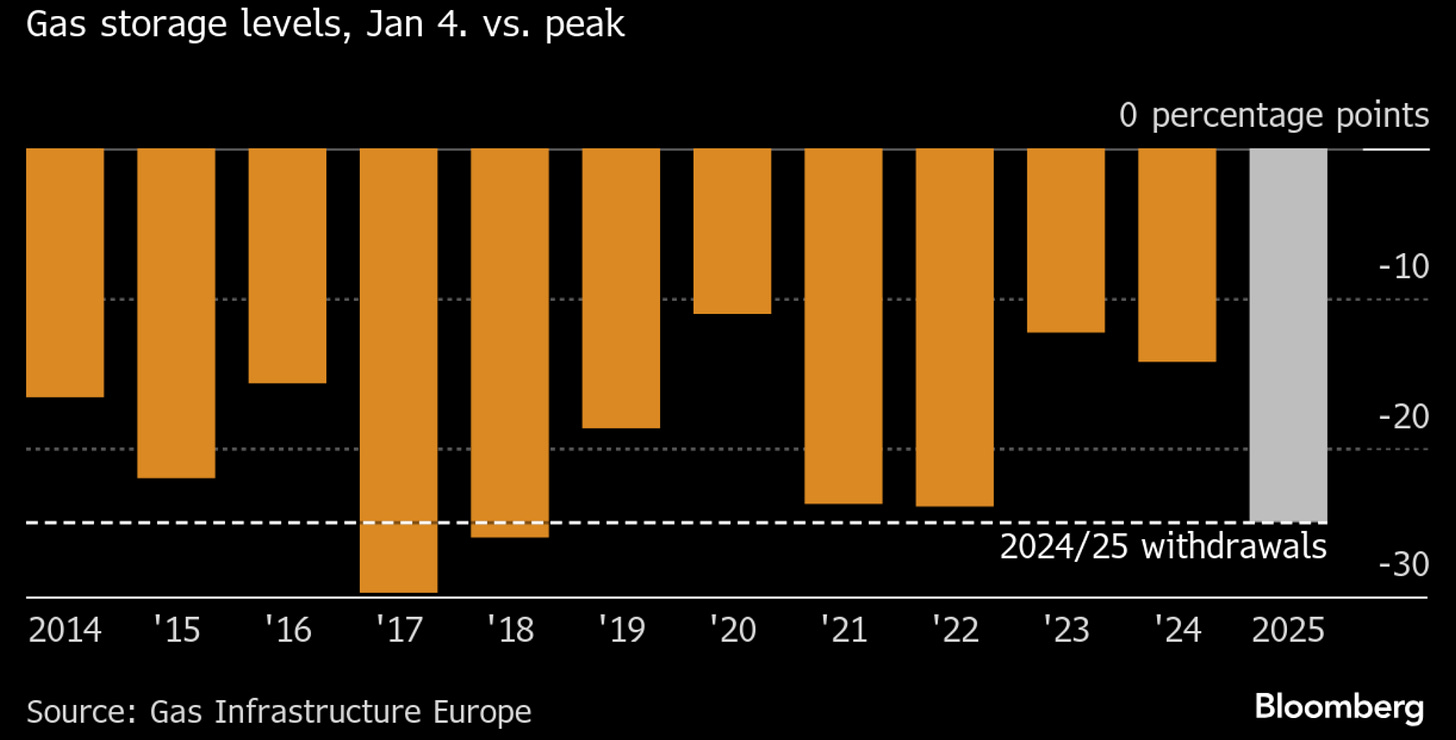

During a prolonged Dunkelflaute, gas storage can drop fast. Europe burned through 25% of its entire storage by early January 2025. That’s why hitting a reasonable amount of storage before winter is critical.

However, right now, storage is only about 55% full. That’s almost exactly where it stood in June 2022, before prices surged nearly threefold by the end of August. In Germany—the country with the most natural gas storage capacity in Europe and also the one most affected by Dunkelflaute—the situation is even worse. Storage is at 47%, well below the 5-year seasonal average of 68%.

The reason storage is low is Europe’s decision to drastically cut gas purchases from Russia. TurkStream is now the only pipeline still delivering Russian gas mainly to Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, and Greece. Everyone else is relying on LNG (though a big chunk of that still from Russia, mind you).

Unlike most pipeline contracts, which lock in prices over long periods, LNG is more frequently traded on open markets with flexible pricing. This makes it easier for hedge funds and other financial players to exploit Europe’s LNG dependency. And that’s exactly what’s happening.

Markets Smell Blood

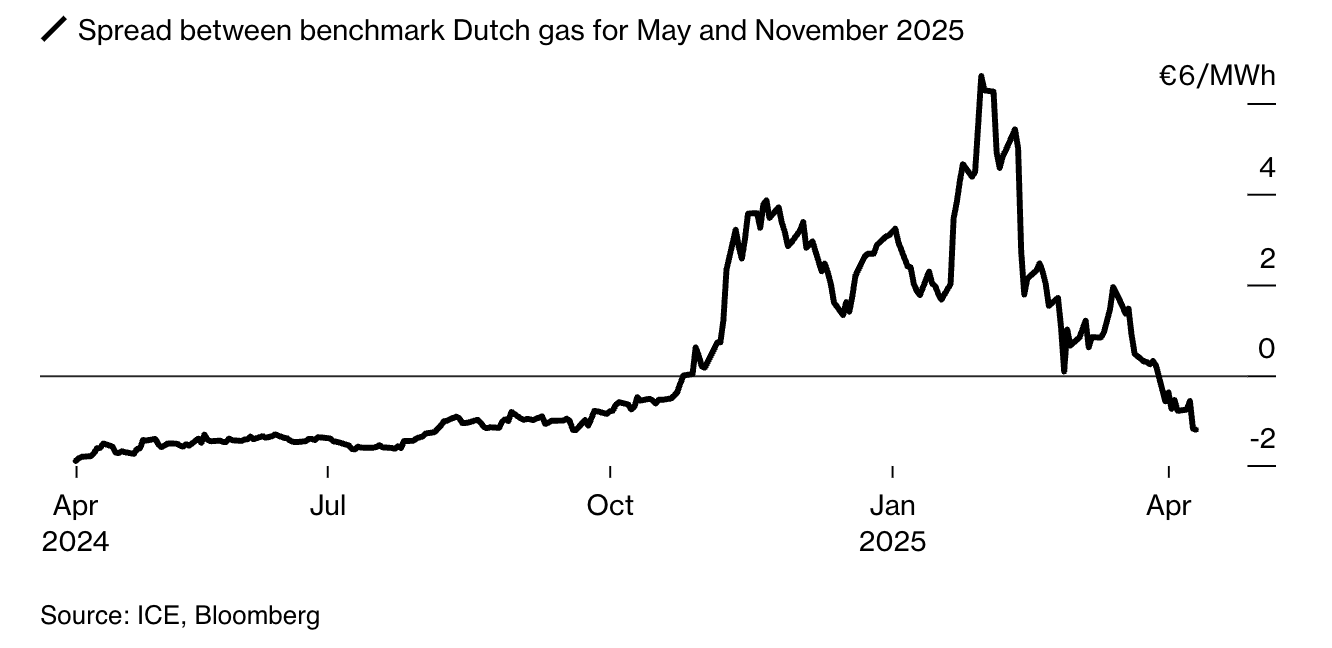

With well-known storage targets, Europe is playing poker with its cards face up. Normally, winter gas contracts trade at a premium to summer ones. Higher demand in colder months drives up prices, giving companies a reason to fill up storage in advance. But that seasonal logic has flipped. In November 2024, TTF summer 2025 contracts traded higher than winter 2026 ones.

In January, things got even worse. Germany’s gas market hub THE said it was in talks with the economy ministry about subsidizing gas storage replenishment if summer 2025 prices remained above winter 2026 prices. The intention was to nudge buyers toward refilling storage. Apparently THE and the economic ministry were under the naive assumption that financial players would somehow fail to spot the gaping opportunity to milk taxpayers by going long on summer prices.

The plan backfired brutally. The usual negative seasonal spread exploded to €6.60/MWh. The spread turned negative again in April as no subsidies have materialized yet. But the possibility of a reversal still looms, especially since Italy launched its own subsidy scheme that same month.

Needless to say it’s common practice for funds to participate in the LNG market. In June 2024, for example, their net long TTF positions hit more than 129 TWh, the highest since January 2022. That’s a massive volume, equal to half of the Netherland’s entire gas consumption in 2024.

A volatile trading environment is a goldmine for hedge funds. Unlike utilities, which earn steady margins from selling gas to end-users, hedge funds thrive on price swings. Volatility is their profit model. So when prices move, they’re willing to bet big. Regulatory caps exist but they allow for massive positions.

Feedback Loop

Under EU rules (MiFID II), a single fund can hold up to 153 TWh of futures outside the spot month. That means six funds could corner positions equal to Germany’s annual gas consumption.

We’re already seeing a ramp-up in speculative activity, based on the most recent data from the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE). Between June 6 and the market close of June 13—when Israel attacked Iran in the early morning—net long TTF future positions of investment funds increased by 25%.

The total volume is still just a few TWh (exact figures are hard to pin down, the market is somewhat opaque). That’s modest in absolute terms, but it’s a sharp uptick in relative positioning and it signals growing conviction.

The danger for Europe lies in the pricing mechanics this kind of buildup can set in motion. Prices don’t move in a straight line during a supply crunch. A bottleneck that pushes prices higher can force short-position holders—typically commercial players—to cover their exposure by buying futures or physical gas.

That, in turn, drives prices up further which potentially creates a feedback loop: rising prices trigger margin calls, which force more buying, which pushes prices up again. This is not only a problem for buyers.

Sitting Duck

It’s a dangerous dynamic for EU leaders. For them, natural gas is political oxygen. Letting the continent go cold or dark would be career suicide. That’s why Europe is paying any price necessary. You could see this in 2022, when some LNG tankers originally destined for Pakistan were rerouted to the UK and Italy. Had the gas gone to Pakistan as planned, it would have sold for about $200 million. In Europe, it unloaded for more than $600 million.

European governments have spent €651 billion to shield consumers from surging energy costs since September 2021. The macro fundamentals for LNG may be less dramatic today than in 2022: demand is lower (mainly thanks to Europe’s deindustrialization) and supply is higher. But even a partial repeat, triggered by supply risk in the Strait of Hormuz, could lead to substantial fiscal spending and deal a serious blow to already weakened industries.

It’s no wonder industry pressure to return to Russian gas is mounting. In March, TotalEnergies’ CEO said:

I would not be surprised if two out of the four [Nord Stream pipelines] came back. There is no way to be competitive against Russian gas with LNG coming from wherever.

But EU leaders were quick to slam the Overton window shut. Two weeks ago, the Commission proposed new sanctions, including an officially block on Nord Stream in addition to its planned blanket ban on Russian energy. None of this will stop the war in Ukraine, as the last three years have shown. All it does is make Europe’s predictable positions easy to exploit. Their rigid stance turns them into obvious targets for funds looking to cash in.

recently pointed out in Fire Marshal Trump that suppressing volatility doesn’t create safety, it creates risk with unpredictable long-run costs. It’s like a forest where small fires are constantly put out until the underbrush builds up so high that one spark burns the whole thing down. That’s what EU energy policy looks like today.Instead of adapting to economic and geopolitical realities, leaders are suppressing volatility with storage targets, subsidies, and moral posturing. But all this patchwork only builds more risk for a major blow-up. The cracks are already visible: fiscal deficits are rising, industries are fleeing, and citizens are getting poorer. At some point that pressure will become impossible to contain. Maybe the Strait of Hormuz will spare the EU this time. But the next spark is waiting.

Share this before natural gas spikes again!

📨 If this was forwarded to you, welcome! The Brawl Street Journal drops once or twice a week. Subscribe now and don’t miss the next one!

Already subscribed? Thanks for helping make BSJ quietly viral.

subsidies for LNG might make gas feel cheaper, but that price delta is made up elsewhere and with interest.

As usual, superb writing.

Germany's energy suicide (energiewende) is their worst policy decision since the 1940s.