Built for Calm Weather

What if Europe redirected renewable subsidies toward domestic gas security?

The most damaging strategic failures often come from collapsing different problems into one and then optimizing the wrong variable. This distinction is obvious in engineering disciplines as old as civilisation itself. Flood defences are not built for the average sea level but for the worst day that might plausibly occur. Designing them for normal conditions produces impressive cost savings, right up until the flood arrives.

Energy security works according to the same principle, even if the analogy is less intuitive. The relevant question is not how the system performs most of the time, but whether it holds when conditions turn hostile. Yet European debates routinely collapse the average and the margin and then optimize the system in a way that weakens it overall.

Consider Europe’s offshore plans unveiled days after the Greenland crisis was temporarily defused. The Financial Times reports:

US President Donald Trump’s threats over Greenland have accelerated Europe’s push for energy independence, officials suggested, as European and UK ministers agreed to build a vast offshore wind grid in the North Sea.

EU energy commissioner Dan Jørgensen said the continent did not want to “swap one dependency with a new dependency”, as it tries to move away from Russian gas but becomes increasingly dependent on fuel shipped from the US.

He made the comments as nine countries with interests in the North Sea, including the UK, Norway, Germany and the Netherlands, said at a summit in Hamburg that they aimed to support a steady build-out of 15 gigawatts of offshore wind each year between 2031 and 2040. The EU wants to meet a target of about 300GW by 2050 — up from about 37GW at present.

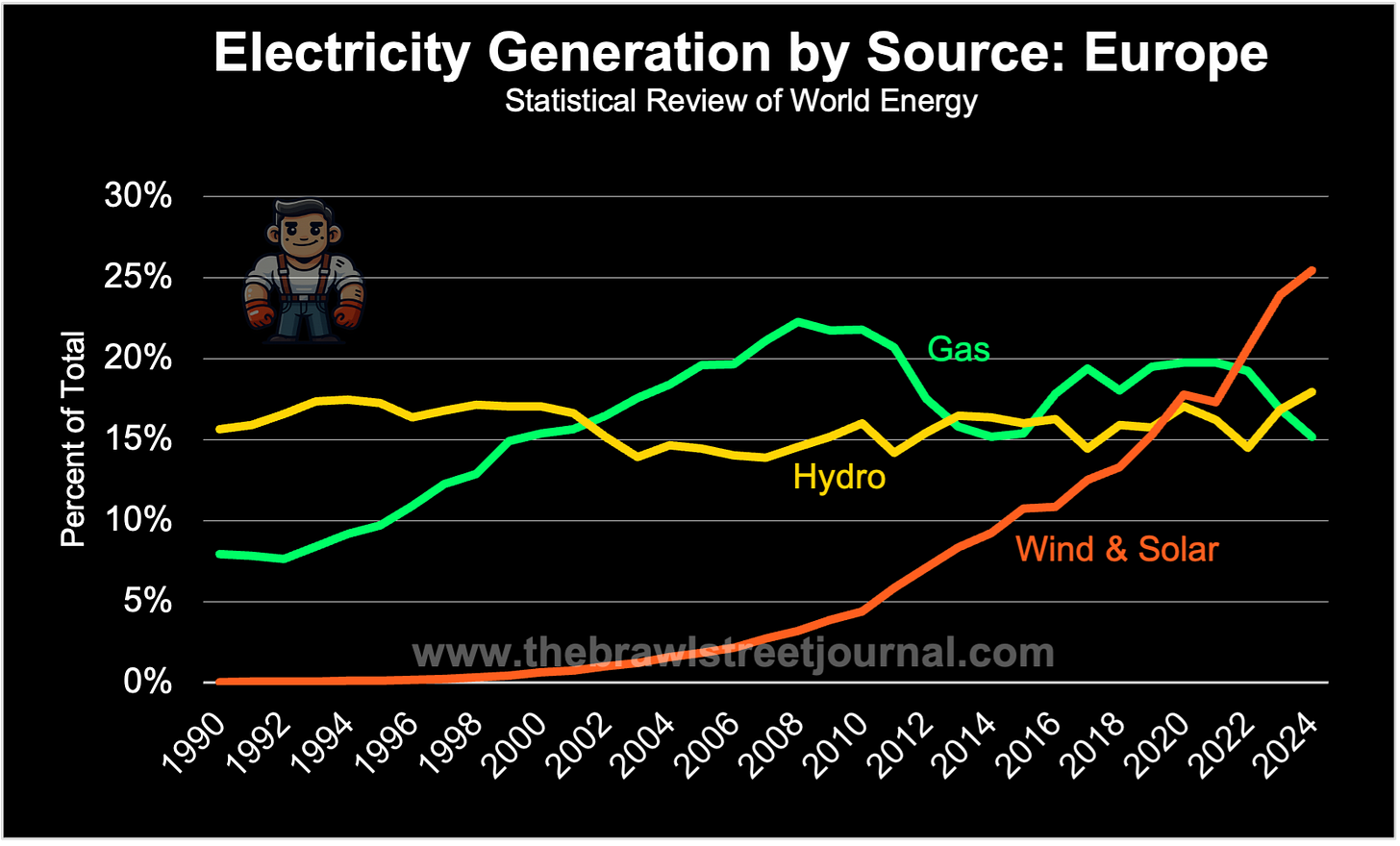

According to the Statistical Review of World Energy, natural gas supplies about 419 TWh of the EU’s 2,795 TWh of electricity generation. From this, policymakers infer that displacing gas with wind power will translate into lower LNG dependence.

On average, this sounds like a reasonable idea. But systems do not fail at the average. They fail at the margin, during tail events when, for example, prolonged cold spells, low gas storage, and a self-inflicted lack of alternatives coincide. Because even if the lights stay on and homes remain heated, industry will begin to pull out of the bloc as rising natural gas prices—a vital feedstock for many industrial processes—render continued operation uncompetitive. And this is before accounting for the risk of gas rationing, which can make production and contract fulfilment impossible altogether.

Not to mention the hard constraint of windless days—precisely when gas becomes indispensable—such as 11 consecutive days of very low wind and solar output in November 2024 across Central Europe, which some advocates argue could be bridged with battery storage. The arithmetic suggests otherwise.

In November 2025, EU electricity demand averaged roughly 8 TWh per day. Green think tank Ember estimates that the total capex for large utility-scale battery storage projects is around $125 per kWh, including equipment, installation, and grid connection. Taking that optimistic figure at face value, 8 TWh of batteries would cost on the order of $1 trillion for one day of coverage. Covering 11 consecutive days would push that figure to $11 trillion. And these figures do not account for degradation or replacement.

Even if battery costs fell by an unlikely factor of ten, the capital required would be measured in trillions, which is why batteries cannot plausibly replace gas as Europe’s stress-case buffer. Of course, 8 TWh represents an upper-bound stress case, as not all regions would be affected simultaneously. But security is priced against worst-case exposure, not median conditions.

In other words, Europe’s gas dependence is not going away anytime soon, as confirmed by Germany’s plans to build an additional 12 GW of reserve gas plants.

That raises a question European policy has largely treated as taboo: is producing gas in Europe more viable than commonly assumed? Under the current Net Zero zealotry, a positive answer to that question seems impossible. But let’s suspend judgment and examine the main objections to ramping up supply, along with ways around them. The scope for moving Europe closer to genuine energy security might surprise many.

The potential for European gas production looks enormous on paper. According to a 2013 energy study by Germany’s Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), Europe’s technically recoverable gas resources amount to 21 trillion cubic metres (tcm).

For reference, the largest producing shale gas basin in the United States, the Appalachian Basin, is estimated to hold around 6 tcm (214 tcf). With the EU’s total gas consumption at 323 bcm in 2024, according to the Statistical Review of World Energy, and assuming 100% extraction efficiency and constant demand, this volume would cover the EU’s entire gas demand for 65 years.

The major constraint is that only 5.2 tcm of these resources are conventional, while 14 tcm are non-conventional. Non-conventional gas can only be produced in sufficient quantities through additional technical measures such as hydraulic fracturing, which involves injecting high-pressure fluid into the wellbore, allowing hydrocarbons to flow to the surface.

Several major oil and gas companies actively pursued gas exploration—particularly non-conventional gas—in Europe during the late 2000s and early 2010s. In 2012, Exxon Mobil’s Central Europe head, Gernot Kalkoffen, said: “(Germany) is most definitely an interesting market. We cannot achieve the energy strategy shift without gas.” With regard to the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, he predicted a 50% chance that fracking might not even be required to bring the gas to the surface.

However, the excitement ultimately fizzled out. Two constraints killed EU gas: politics and economics. Public opposition to fracking led to bans in several countries, including Germany, France, Bulgaria, and the Netherlands. Major concerns centred on groundwater pollution, as well as fears of earthquakes. These concerns are not entirely unfounded, given that the municipality next to the Groningen field, Europe’s largest natural gas deposit, still suffers from earthquakes even though production ceased in 2023. Notably, Groningen was a conventional field and did not involve fracking.

The economic constraint is straightforward: domestic gas has rarely been cheap enough to justify drilling when imported supply was readily available. According to the Institute of Energy Economics at the University of Cologne (EWI), the cost of extracting shale gas in Germany ranges between €25 and €42 per MWh. The Center for European Economic Research (ZEW) estimates that fracking becomes economically viable once gas prices exceed €50 per MWh. That estimate dates from 2013, and inflation since then has likely pushed the threshold higher.

Prices at the Dutch TTF—the benchmark for landed LNG in Europe—have mostly fluctuated between €30 and €40 per MWh over the past two years, with brief periods near €45–50 and lows around €27–28. At those levels, gas exploration in Europe has been a poor business case.

However, energy security is a public good. The question, then, is whether public money is being spent on the wrong solution, or whether it could be used more effectively. To answer that, it helps to look at the EU’s renewable subsidies, which do little to strengthen security at the margin. Between 2021 and 2023, renewable energy subsidies ranged between €61 billion and €83 billion per year.

Note that these figures cover only subsidies spent directly on installed capacity. Once grid expansion, storage, and frequency control are taken into account, it is reasonable to assume that the total system cost doubles going forward. Coincidentally, this is also what UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called for.

For ease of calculation, let’s ask what €100 billion of taxpayer money used to bridge the price gap between market gas prices and economically viable fracking in Europe would unlock. Given inflation, let’s set that breakeven threshold at €70 per MWh.

If economically viable fracking requires a gas price of roughly €70 per MWh, and the market price at the Dutch TTF has hovered around €35 per MWh, the subsidy required is about €35 per MWh. A budget of €100 billion deployed to bridge that gap would therefore underwrite roughly 2.9 billion MWh, or about 2,850 TWh, of gas production. Converted into volumes, that corresponds to roughly 270 bcm of natural gas—close to an entire year of EU gas demand at current consumption levels—once capital has been deployed and learning effects have materialized.

The exact figure naturally varies with market prices, but the order of magnitude does not. Redirecting sums spent on renewables could, in principle, buy Europe a very substantial buffer of domestic gas optionality. Some price feedback is inevitable: subsidizing domestic gas production would depress market prices and require larger subsidies. But that is how tail risk is reduced and industrial shutdowns are avoided. Resilience is never free.

The next obstacle is, of course, public opinion. Protests in densely populated Europe have real impact and this opposition is rational: local communities bear the noise, traffic, and risk, while the benefits flow elsewhere. In Europe, mineral resources are usually owned by the state, so affected communities see few direct benefits from drilling.

In contrast, in much of the United States, landowners own mineral rights and receive direct royalties from drilling. Disruption comes with upside. Europe’s approach would have to be substantially reworked so that communities directly affected by drilling also share in the gains when projects succeed.

The third and final policy relates to the legal standing of green NGOs, which can delay projects almost indefinitely through nuisance claims. Projects of strategic importance should not be stalled by actors who bear no system-level cost. The rules governing legal standing therefore require serious reform.

Redirecting policy in this direction would materially advance Europe’s much-invoked “strategic autonomy.” The constraint is not feasibility, but political will. Ultimately, power accrues to those who control resources and are willing to deploy them. As long as Europe chooses to leave its own potential untapped, it will continue to carry its most dangerous tail risks forward.

Share this with anyone who thinks averages are what matter!

📨 People in boardrooms, energy desks, and hedge funds keep forwarding this. Stop getting it late — subscribe now!

Already subscribed? Thanks for helping make BSJ quietly viral.

Excellent piece, as Doomberg has written many times, politics has been the bottleneck all along, not geology. It's interesting, one of the things the Trump administration has been doing. that gets far less press is the overturning of environmental regulations that will reduce the scope of the constant lawsuits from climate organizations whose goal is simply to waste time and drive the cost of production higher accordingly. if those organizations no longer have standing to sue, more positive energy outcomes are virtually guaranteed.

But you also highlight the different property rights issue between the US and Europe, and that is a much tougher issue to overcome.

Alas, I suspect that reliability and security of energy resources will need to degrade far further before any political changes are possible.

Great article.

I love that image showing the gas basin reserves across Europe—I had no idea. They are currently inaccessible due to a lack of political will (as you said), but as the old saying goes, “things stay the same until they don’t.”

Redirecting renewable subsidies to fund domestic gas production—100% agree, but it might be easier to convert Europe to Hinduism than to get them to let go of that secular religion. But I hope I’m wrong.